|

kitarist -> RE: Can a white man play the blues? (Jun. 18 2021 7:26:44)

|

Sorry, I got sidetracked by real life; will try to catch up on replies in one post.

quote:

ORIGINAL: Ricardo

quote:

An explanation just occurred to me - it is precisely because Borrow takes so much pride in his deeper knowledge and understanding of gitanos that he does not himself refer to gitanos or their art as 'flamenco'(*) - he knows they are not Flemish and thinks he knows it was a confusion that started this labelling;

The point is, he quotes them and the term was not used. Even by toreros. I can understand himself avoiding it on principle but NOT the people he interacted with and quoted. [] I mean he is very explicit so either it wasn’t used or he deliberately didn’t want his readers to know it was used

I take this to mean that it was not used or preferred by the gitanos themselves at the time, and this is why he did not use it. One might say “ What about the ‘flamenca de Roma’ in the copla?” I feel like it is not enough to deduce from it that ‘flamenco’ as a term was in general use by gitanos themselves. One reason is that Borrow is very explicit about how others call gitanos versus how they call themselves, and ‘flamenco’ doesnot appear in the latter category. Secondly, in introducing the poetry of the gitanos, Borrow says (The Zincali, vol.2, p. 8-9):

“Many of these creations have [] been wafted over Spain amongst the Gypsy tribes, and are even frequently repeated by the Spaniards themselves; at least, by those who affect to imitate the phraseology of the Gitános. Those which appear in the present collection consist partly of such couplets, and partly of such as we have ourselves taken down, as soon as they originated []”

And

“These couplets have been collected in Estremadura and New Castile, in Valencia and Andalusia; [] they constitute scarcely a tenth part of our original gleanings, from which we have selected one hundred of the most remarkable and interesting.”

“Flamenca de Roma” could have been part of the coplas “repeated by the Spaniards”, however massaged (by them) in the process of doing so, possibly by including that strange phrase "flamenca de Roma” which does not occur anywhere else – it sounds like others speaking of gitanos or of practitioners of the art and clarifying - rather than gitanos speaking about themselves. (Also, the fact that this is a curated selection which is 10% of the original – and yet ‘flamenco' occurs just once in that strange phrase - for some reason makes me more certain gitanos were not using ‘flamenco’ to refer to their art or its practitioners/themselves)

quote:

ORIGINAL: Ricardo

quote:

OK, what about cantes/bailes like caña, polo? For example, the 1604 reference is to a caña.

[] This means that in the same manner that seguidillas are NOT flamenco Siguiriyas, neither are the polos THE Flamenco polo as we know it. I further suspect the referenced cañas are equally not flamenco Cañas, and in fact I now feel all three names were stolen, like we know Guajiras rumba tango etc are only names, but stolen and used as convenient titles to “flamenco” songs, for no musically specific reasons. It is a habit we see, and thusly we can assume there is no reason to assume printed names of forms are in fact the flamenco ones we know.

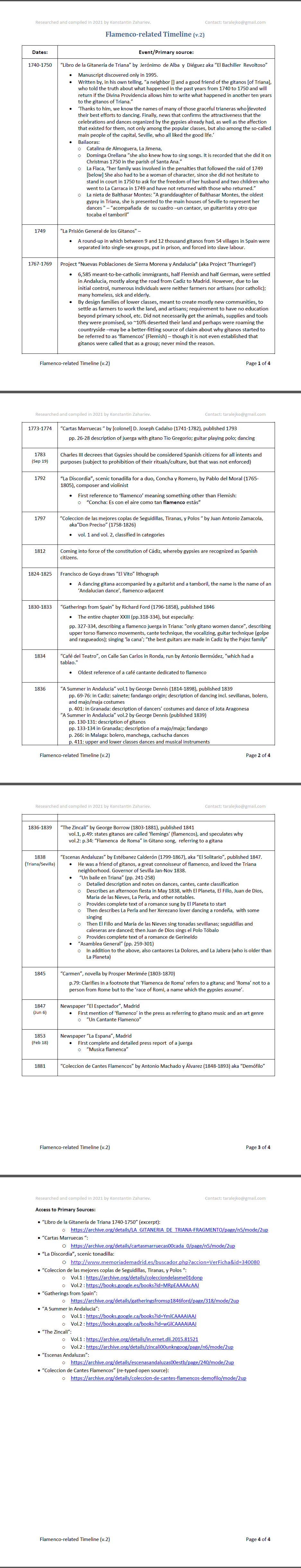

OK so just to confirm here - does this mean I should remove the 1797 Zamacola volumes from the timeline because the seguidillas, tiranas y polos described there are in fact not flamenco-related?

quote:

ORIGINAL: Ricardo

The 1740 book is 7 pages of sloppy hand, so only one page of info doesn’t reveal much more than the bullet points you supplied. (Glad I did not purchase the 30e facsimile!😂)

No, actually this was just the excerpt that I could find – which is maybe 10% of the entire manuscript. Google and others give the total pages of the book as published in facsimile as around 70-85 pages which includes the transcription.

I was actually very keen on buying it but can’t find the thing anywhere – it seems out of stock. The additional material from it that I provided I gleaned from research papers quoting from it.

BTW did you read through the Ford book “Gatherings from Spain” circa 1830-1833 – especially chapter 23, pp.327-334, the juerga in Triana? The book is written in beautiful English; it is a pleasure to read. But also any comments on “the best guitars are made in Cadiz by the Pajez family”? – Anyone heard of this family and their guitar making?

Now more potentially interesting books:

1. From Christmas 1649 in Jerez (!): “Villancicos que se cantaron en en la Iglesia de San Miguel de Jerez de la Frontera en la Navidad de 1649” (“Christmas carols that were sung in the Church of San Miguel de Jerez de la Frontera at Christmas 1649”), compiled by Francisco Barbosa:

https://archive.org/details/VILLANCICOJEREZ1649/mode/2up

Only 8 pages but I am wondering if any part of the songs are recognizable today as part of saetas, for example?

2. From 1870: “El gitanismo: historia, costumbres y dialecto de los gitanos. Con un epítome de gramática gitana” (“Gypsyism: history, customs and dialect of the gypsies. With an example of gypsy grammar”), by Francisco de Sales Mayo:

https://archive.org/details/elgitanismohist00mayogoog/page/n10/mode/2up

3. From 1915: “Historia y costumbres de los gitanos, colección de cuentos viejos y nuevos, dichos y timos graciosos, maldiciones y refranes netamente gitanos ; diccionario español-gitano-germanesco, dialecto de los gitanos” (“History and customs of the gypsies, collection of old and new stories, funny sayings and scams, curses and clearly gypsy sayings; Spanish-Gypsy-German dictionary, Gypsy dialect”) by F.M Pabanó:

https://archive.org/details/historiaycostumb00pabauoft/page/n7/mode/2up

|

|

|

|