|

Ricardo -> RE: 19th century spirit guitar (Jan. 29 2023 20:57:19)

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: estebanana

Fantastic essay, the author is so polite in how she refutes the assumptions of previous writers. I think this painting hits on the fact that Sergeant was a true aficionado, and I’ve always thought this picture is quite true to 19th century flamenco as a daring foreign aficionado would have seen it in a fairly hardcore venue.

Please bring forth anymore gems on this subject you have archived.

If I may put forth some thoughts on the painting, and the observations of the author linked above.

First, it is echoed again the thing about gitanos being all the same class of individual, and negates that the stewards of flamenco music often had successful work, and integration, even some were bullfighter celebrities. So I am not keen on the “flamenco as a form evolved in the caves” type of thing. But it is so common it is not a big deal. All of her observations are right on about what is in the painting but she misses out on few opportunities to point out details, which I would like to add now.

Castañuelas: Correct she does not have them, and probably shouldn’t (Carmen Amaya used them in Siguiriyas etc., but it was considered unusual even then). But the proof is beyond the painting itself. I have the book that shows dozens of sketches as studies for this work that show the hands, palms empty. He used the same exact dancer and pose several times so, he was not trying to paint a literal scene from memory (in a sense, yes he is inventing things in the picture, as real as it looks). Likely her left hand is doing pitos (snapping) like the seated girl. The other hand is not grabbing the skirt (as the author claims) put is palm open, wrist pushing against hip. All the sketches show this.

Jaleo: This word has several meanings related to flamenco, and the issue is which one of these did HE intend. There is a clue on the wall on the back. “Ole” is written deliberately. This means “Jaleo” is referring, in his mind, not to a song form, but to the literal shouting out loud. This is done in any palo at any time (ideally in compas on the 12, or downbeat feeling), but the painting also shows activity that implies one of the other meanings of the word, which is the music that is performed in the Juerga or Fin de Fiesta. This music is typically, bulerias, OR tangos, etc., ie, up tempo forms. The posture of the palmeros is of this type of rhythm, not a solea or siguiriya, or even a fandango. Specifically the man on left, and girl on right are on the beat, and the man on the right in the middle, is doing the contratiempo.

I have seen the label “Jaleo” used for both Buleria and Tangos, so, a synonym for “juerga or fin de fiesta”. In American English we can think of the word applying to music that is played at an “after party”. A non-flamenco example would be Mozart and his opera friends post concert shin digs in the Amadeus movie. I feel the setting of the painting is intended this as well, rather than a tablao or theatre show. So for me, these two meanings apply to the painting (juerga and shouts of encouragement that goes with it). The other meaning is the song form. Castro Buendia has an interesting paper on the subject and relationship to the Soleá. However and ignored aspect is the Extremeño melody connotation of the word, and is how today working pros apply the term. The melody also comes with rhythmic baggage (does not have to), and we addressed this specifically in the cante accompaniment thread with examples of Jaleo accompaniment. I don’t think the painting needs that extra meaning, but it can in theory apply to what might be sung or played (Buleria Extrameños specifically, and the guitarists give a clue there, but could be coincidental of course).

For the record… the melody on Norman’s site called “Jerez Anonymous” is the specific one we associate “Jaleo” with today. There was a thread about a book that catalogues the various melodies of Extremadura for a more complete picture. I have to say, the idea that the “jaleo” as a song form (Buendia focuses on Jiliana, as female and Jaleo as male in terms of dance of the same music) pre-dating Solea makes no sense to my musical brain. As we see the enormous amounts of cante derivatives of Solea family, Jaleo fits as a subset of the family…not a precursor ancestor. IMO of course, it is just not logical. Again, historians are more concerned about the word itself and its appearance in print since music score is not in print to clarify. Printed music implies different music using the same titles (and is a waste of space in much of Buendia’s work IMO, yet he takes it as evidence the cantes likely did not actually exist yet, at least as we now think of them).

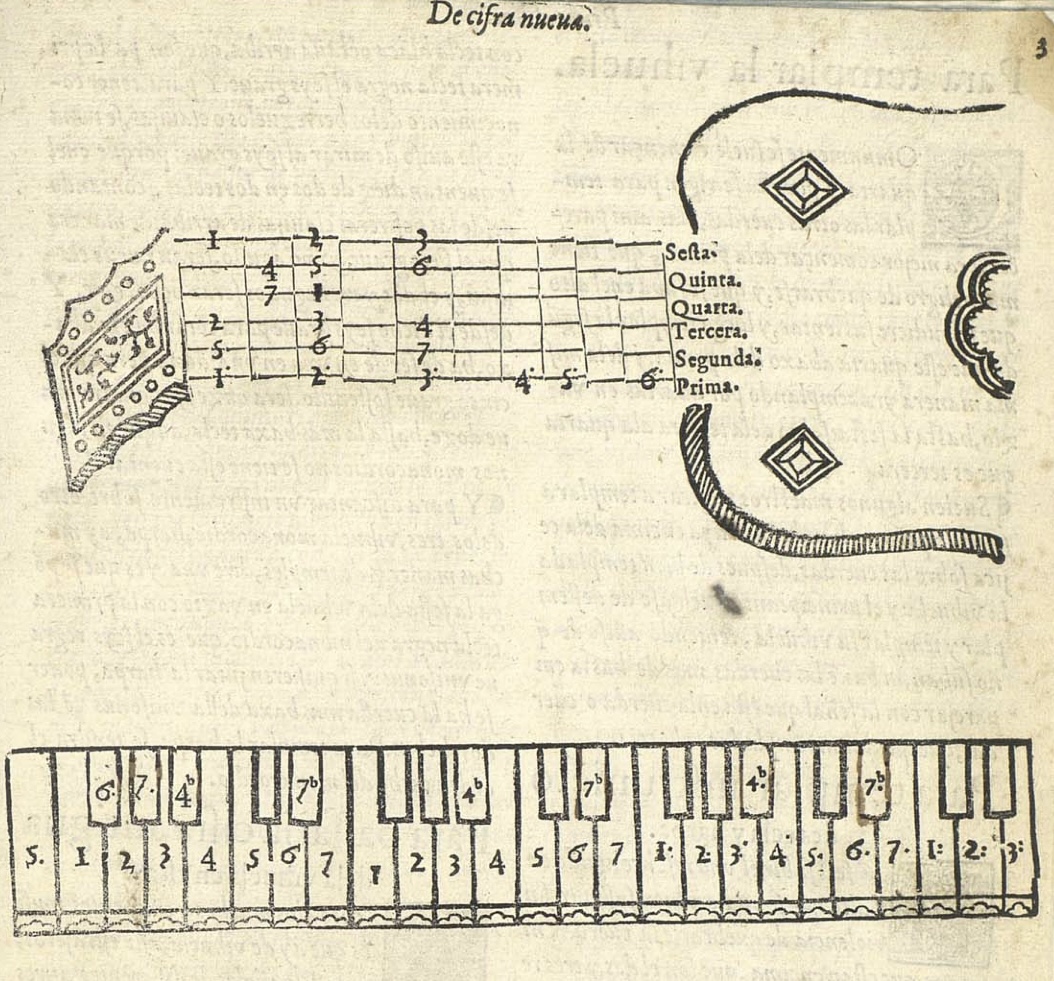

Guitarists: even though his guitars kind of suck interms of realism, I also have sketches of other guitar players of his, and it is obvious he plays guitar himself, and could very well be representing chords he actually knew were being played in the moment. One sketch shows two players using an E major triad, and in this painting we discuss, they are playing a high position C9 and C13 respectively. That pinky reach of the player on the left is the same type of voicing Tomatito uses in a buleria falseta in Encuentro. PDL uses it as well. The high position implies they are probably using capo at 4ish, though it is not clearly visible. Otherwise an absolute pitch chord of E9, and E13 could be in play, but I doubt it. Both players are using open handed abanico. The chord would be the correct harmony for Buleria Extremeños first line of verse (probably coincidence). I know it is not the cambio chord because the dancer is not doing the typical remate for that part of the letra. The capo 4 implies a high tessitura for the singer, which leads us to his head position.

Singer: There are two modes of vocalizing. Opera singers drop the larynx and tilt forward as pitches rise, and this is visible in the actual neck of males where the adams apple protrudes as pitches rise. Many pop and rock singers use their speaking voice to sing, and this means the larynx bobs up or down based on pitches just like speech patterns. For high pitches the larynx moves uncomfortable high and to compensate, these singers noticeably lift the chin. Lemmy of Motörhead, Brian Adams, Ariana Grande, are obvious examples. Steve Perry tilts his head sideways to make room, as an alternative. To me, the guy in the picture is demonstrating this exactly, and the high chord position reinforces this possibility (4 por medio). Also the high pitch of the melody is on the first line of verse (the others fall to tonic usually). Today many flamenco singers use lower titled larynx so you don’t see that action.

Last observation is the chair. The guy has a guitar in the lap next to the chair. I suspect the dancer might have been using the guitar, and handed it to that guy who was eating an orange, and he put it down so she could dance a patada por Bulería. Of course, that is speculation but makes sense.

|

|

|

|