Welcome to one of the most active flamenco sites on the Internet. Guests can read most posts but if you want to participate click here to register.

This site is dedicated to the memory of Paco de Lucía, Ron Mitchell, Guy Williams, Linda Elvira, Philip John Lee, Craig Eros, Ben Woods, David Serva and Tom Blackshear who went ahead of us.

We receive 12,200 visitors a month from 200 countries and 1.7 million page impressions a year. To advertise on this site please contact us.

|

|

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco

|

You are logged in as Guest

|

|

Users viewing this topic: none

|

|

Login  | |

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito)

|

|

|

quote:

The facsimiles are the concrete examples. Zayas is a translation into modern notation(?) or cifra(?). Hudson points all this out.

Can’t believe you are still beating around the darn bush. NAME ONE PIECE that moves chords on weak beats to took at, that suggests FANDANGO compas is not original before Ocon vs Abandolao. The facsimile is included, plus more modern tabs, plus his special f’d up notation where big note heads are an octave lower than smaller note heads. Have no fear, I will correctly interpret the score once I know what piece I am supposed to be looking at!!!

quote:

I am not familiar with Maximo Lopez.

Well, shame on you. But I guess you were not paying attention a few years back. It is one of two pieces of flamencological evidenced I thanked YOU for pointing me towards, and was surprised existed. Which brings me to the second:

quote:

The Ocon has next to nothing in common with accompaniment in the earliest recordings except for the a-b-d c-e-g f-e-f figure that could be used in escobilla or as a falseta.

Double shame on you, as you turned me on to Buendia and again I was surprised. I am surprised also by the interpretation of the evidence. And it is clear you are following that line. If you want to go further, he equates that falseta to (holding back my laughter) a Sabicas Jaleo, to prove his case that Jaleo predates the Soledad. Sorry Soledá. Ok, I agree to disagree about the interpretation of the evidence.

quote:

only that they use the term to describe song and dance that we impose our concept of flamenco on and then confirm our bias.

yes, well, it took me 20+ years to be able to get to a level of which I could “confirm my bias” by interpreting the evidence in the manner of discarding what is irrelevant vs what is. I said multiple times “formal structure” and why historians ignore the importance of the two pieces of evidence I keep emphasizing, is simply that they don’t have this “confirmation bias” subjective vantage point that 20 some years of hardcore immersion and study provides. You should find yourself in similar position, but due to what I see as “red tape” in your research field have fallen into a different type of “confirmation bias”….the other end of the spectrum where all evidence is weak and adds to the pile collectively. Oops. You know that in order to interpret any of the evidence differently, from a more practical and informed position, the mountain of crap evidence that you would have to address just be taken seriously is beyond daunting. “Sabicas jaleo” Huh? The basic thing? How did that get through a “peer review” is what I don’t get. You admit the falseta in black and white there is “more than that” in the previous quote. The damn piece is even called “Soledad”. Like, to UNDO THE MESS already made around the interpretation, one would need to start every reader at the damn beginning dance class, ie “first principles”. But then you admit, due to anthropology influence, they want researchers hands off??? Dead end. C under a sung B. Great. Forrest. Trees.

quote:

Concepts carry loads of assumptions.

For practical reasons I agree with you...for historical and cultural reasons I do not.

Aren’t you always pointing out practice vs. theory? That the practice itself is the context and the theory is a way to explain it not vice versa? Why does the older time period and different country (Italian renaissance) flip the situation, and suddenly “chord” is a dirty word for anyone to use to simplify the concept? I get that the students, forced by some priest to “think” a certain way about voice leading, instills a thought process ON PAPER. But those teachers don’t have the final word, it is just a singular approach. You admit what is learned in university is different…well it went through a process to simplify concepts the way I see it. Just look at the moving cleffs. The only reason for all that complexity is to avoid ledger lines!  And interms of voice leading rules, yes there were general rules that had validity that give rise to tonal harmony function, but meanwhile you see all kinds of disagreement back then that in hindsight is obviously silly, because it is just semantics. Just like Bm7b5/F vs Dm6/F, etc. etc. And interms of voice leading rules, yes there were general rules that had validity that give rise to tonal harmony function, but meanwhile you see all kinds of disagreement back then that in hindsight is obviously silly, because it is just semantics. Just like Bm7b5/F vs Dm6/F, etc. etc.

But since the F6 Dm7/F thing is a point of issue, and it is relevant to flamenco too in a way (if we are going to an E resolution that is  ) maybe we should discuss a concrete example? ) maybe we should discuss a concrete example?

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 1 2023 12:35:27

|

|

Romerito

Posts: 45

Joined: Jan. 18 2023

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

quote:

Can’t believe you are still beating around the darn bush. NAME ONE PIECE that moves chords on weak beats to took at, that suggests FANDANGO compas is not original before Ocon vs Abandolao. The facsimile is included, plus more modern tabs, plus his special f’d up notation where big note heads are an octave lower than smaller note heads. Have no fear, I will correctly interpret the score once I know what piece I am supposed to be looking at!!! We're writing past eachother. I haven't been concerned with fandangos but many of the pieces in Sanz and de Murcia make changes on metrically weak positions. Sanz, Passacalle por la E is just one example. Historically informed performers like Rolf Lislevand are good sources to hear the music and follow the score. It also occurs in Jacaras and other genres. Have not found a fandangos like you are looking for.quote:

Well, shame on you. But I guess you were not paying attention a few years back. It is one of two pieces of flamencological evidenced I thanked YOU for pointing me towards, and was surprised existed. Which brings me to the second: LOL!

Do you know how much I have read? If I don't remember Lopez it is because there are many things I have since read. I also do not get on the foro much for this very reason. I think you should write something and present it to peer review.

They accept independent scholars' work all the time. Don't do an ethnomusicology journal of course, but music theory or history...definitely. quote:

Double shame on you, as you turned me on to Buendia and again I was surprised. I am surprised also by the interpretation of the evidence. And it is clear you are following that line. If you want to go further, he equates that falseta to (holding back my laughter) a Sabicas Jaleo, to prove his case that Jaleo predates the Soledad. Sorry Soledá. Ok, I agree to disagree about the interpretation of the evidence.

Double LOL!

I get it. You don't like academics. You should write your own historiography.

Soledad is fact. It existed before the solea. quote:

yes, well, it took me 20+ years to be able to get to a level of which I could “confirm my bias” by interpreting the evidence in the manner of discarding what is irrelevant vs what is. I said multiple times “formal structure” and why historians ignore the importance of the two pieces of evidence I keep emphasizing, is simply that they don’t have this “confirmation bias” subjective vantage point that 20 some years of hardcore immersion and study provides.

What is your evidence for that? You know Gamboa and Castro Buendia, and Nunez and many others started as flamencos. Some continue as amateurs but they live, eat, and breathe with flamencos year round in Spain. They speak the langauge and are steeped in Andalucian culture. Damn bro...I know you are an accomplished accompanist and have a solo CD but just wow! Nobody else has been doing this 20 years. And no one has a head start on the historiography aspects. and no one has immersed themselves in the art form?quote:

The damn piece is even called “Soledad”. Like, to UNDO THE MESS already made around the interpretation, one would need to start every reader at the damn beginning dance class, ie “first principles”. But then you admit, due to anthropology influence, they want researchers hands off??? Dead end. C under a sung B. Great. Forrest. Trees.

Peer review corrects itself. There will be other scholars who call him on it and he can then correct it if in fact he is wrong. Your ideas are not even being peer reviewed except here, which is an unfair arena because most people put you on a pedestal. quote:

Aren’t you always pointing out practice vs. theory? That the practice itself is the context and the theory is a way to explain it not vice versa?

No. We keep talking past each other because we do not share a vocabulary. Your use of the word discipline, for example. In scholarly contexts that has a specific meaning having to do with area of study. Music and musicology are disciplines, flamenco would be a focus or field which could be treated to musical or musicological study.

quote:

I get that the students, forced by some priest to “think” a certain way about voice leading, instills a thought process ON PAPER. But those teachers don’t have the final word, it is just a singular approach. You admit what is learned in university is different…well it went through a process to simplify concepts the way I see it. Just look at the moving cleffs. The only reason for all that complexity is to avoid ledger lines! And interms of voice leading rules, yes there were general rules that had validity that give rise to tonal harmony function, but meanwhile you see all kinds of disagreement back then that in hindsight is obviously silly, because it is just semantics. Just like Bm7b5/F vs Dm6/F, etc. etc.

It is not just semantics. Or if it is, it is English vs Latin vs Spanish semantics. Jazz has spoiled theory (not for jazz) because anyone who studies a bit then thinks they can apply the theory to anything they want. Same for the four semester theory track.

If you have time, check out the partimento guys. That practice is different and the theory is different. If a practice is different than another practice then how can its theory be the same?

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 1 2023 18:00:25

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito)

|

|

|

quote:

Sanz, Passacalle por la E is just one example.

Thanks. Again, the reason for the Fandango focus was about “rasgueado vs punteado” conceptually. Ocón is a great under emphasized source because a lot of our flamenco basics are in there, yet it is underemphasized as “possibly not proper-flamenco, yet is shown because it is in-a-proto-transitionary state of being, so i can make my conclusion that Silverio invents what we think of as flamenco otherwise I have to account for this Ocon junk”, type of evidence.

You said he (or me quoting the book) had it “backwards” as a concept regarding rasgueado and punteado, implying that “fandango” (probably not the same thing as what I want to think of as fandango but ok), already has the rasgueado and punteado going on in Baroque era, much earlier than we are supposed to infer the time frame Ocon is discussing. There are some Mexican and Peruvian examples on the previous page that have the 6/8 feel mixing 3/4 accents against that general feel. I am not talking about THAT if that is what you might mean. I mean like Seguidillas Manchegas type of Off set chord moves from the pulse.

quote:

Soledad is fact. It existed before the solea.

The word. Not the FORMAL STRUCTURE. Buendia points out a classical piece for strings called Soledad in the major key, referencing gypsies. Meaning, a classical musician wrote a piece referencing gypsies, and called it “Soledad” VERY LIKELY BECAUSE THEY WERE DOING SOMETHING CALLED THAT, or it was a person’s name, or something, who knows. When the word appears in newspapers in the 1850’s, it is not clear which Soledad is referred to because obviously in 1856 you have Planeta (a known flamenco singer as per oral tradition and blood lineage, like it or not), and Ocon showing a DIFFERENT SOLEDAD. Buendia wastes a lot of ink pointing out the other pieces that rip off Ocon’s melody, etc. But at the same time misses the forest that Ocon shows solea proper in every way I can explain as a professional artist. That to me is fact, but I can’t seem to get past interpretation.

To me here is the basic math…Ocon does NOT EQUAL the OTHER classical piece called Soledad. There is not other musical piece to confuse, or claim as a transition piece or music, so therefore no reason to point to “surface similarity” to jaleo or whatever, diverting the issue towards some OTHER music that will “Later become” what we know as solea. This coupled by the basic fact that even well into the 1900s and today palo form names get swapped all the time except by very nerdy aficionados that try to keep it all well labeled, points to a situation that the “solea” was simply not called THAT in the time of Estebañez Calderon, OR, he simply missed it and doesn’t talk about it (doubtful once you understand flamenco properly from my perspective and the central importance the form has). A third math fact is that Solea is huge and Caña/Polo is very very small in comparison as a genre of cante, yet they share the same compas? That should explain a lot, but I guess it does not for people. What it means is, it does not make musical sense that Caña came first and Solea derives from it later on. Seated in the Ocon book next to each other is not coincidental, nor that the entire section of pieces has a relationship as what we today know as the the genre of flamenco. Seguidilla Sevillana and Contrabandista (Garcia Lorca either created Anda Jaleo from that or learned it from people that did) could loosely fit in with those, and Zapateado too, but in the same way we practically think of the separation today. The only thing not terribly relevant is all the polo Tirana stuff in the book. Felix Maximo Lopez fandango copla fits in with what Ocon shows, and I believe Arcas or Aguado has the fandango copla as well, however we don’t even need that because they are not showing flamenco guitar stuff. All this points to “it existed”. And by “it” I mean the formal basis structure of the enormous branch of cante called fandango copla. 1800 LATEST. Estebañez Calderon also admits it is old stuff they are preserving (old music IN 1838), which implies Caña/polo and with them the Soleá whatever it was called. Could have been Romance even.

quote:

You know Gamboa and Castro Buendia, and Nunez and many others started as flamencos.

Here, i don’t want to be rude. All respect to them, and all seem like very nice humble guys (unlike me the exact opposite LOL). I played side by side with Gamboa in Gerardo’s classes/juergas. Late nights, hours and hours. He would not be comfortable in the professional shows I have done. Castro buendia, I don’t know, I saw him play a classical piece on YouTube. I see his scores and read his words. I like him, but am confused otherwise and therefore, by some of his interpretations. Nuñez sings and plays in his lectures. That should basically tell his level.

They are free to explain things and put things forward as they see it. I can’t say how deep is their understanding in the same way as when I am on stage or in rehearsal with artists, and their levels are clearly demonstrated and in your face. I basically have their words to go on and my own subjective experience of which to contextualize whatever they claim. The thing the Solers did/do, this guy Chavez that made the book with Norman, and Norman of course, they know their stuff and a profoundly deep way beyond my practical knowledge, and I therefore learn from them. However when they put forward a claim, I don’t notice any problems either, and trust me I am on the look out. For example in Chaves cante mineros, once my ear is oriented to a certain style I read the label for this other cante and hear it and go “hey, That is the same Cartagenera thing!”…but sure enough in the text he points out this exact thing. So, some guys involved that don’t use music really know what is going on. I extend this same expectation to the three guys up there, and I don’t always see the same rigor in their text. Unfortunately, The solers are not able to review Ocon etc., as they don’t use scores. Fandango is blues? Ok, if you say so, I can’t read music.

quote:

Your ideas are not even being peer reviewed except here, which is an unfair arena because most people put you on a pedestal.

All I ever do is argue on here!   Few people ever blindly agree with almost anything I have put forward that is a little “different” than the typical view. Few people ever blindly agree with almost anything I have put forward that is a little “different” than the typical view.

quote:

Music and musicology are disciplines, flamenco would be a focus or field which could be treated to musical or musicological study.

You mean academics. I mean guitar genres in practical terms. Different genres of music have their own system for learning or operating and terminology. I have always been clear about this. A field is a wide open grass area where animals graze. It only relates to flamenco if the animal is a bull. Focus is when you visually zero in on something. None of that has to do with translating terminology for the same basic operation between two genres.

quote:

If you have time, check out the partimento guys.

I have. I don’t see how it is different, other than terminology and rules, bottom up instead of top down, Improvisation vs composition, etc, from Franco-Flemish polyphony or other ecclesiastical part writing music. Maybe if you briefly bullet point the differences then I might see how it is relevant that I can translate one into guitar chords easily, and NOT the other, and then why that is relevant to spain and flamenco.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 2 2023 13:17:29

|

|

Romerito

Posts: 45

Joined: Jan. 18 2023

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

quote:

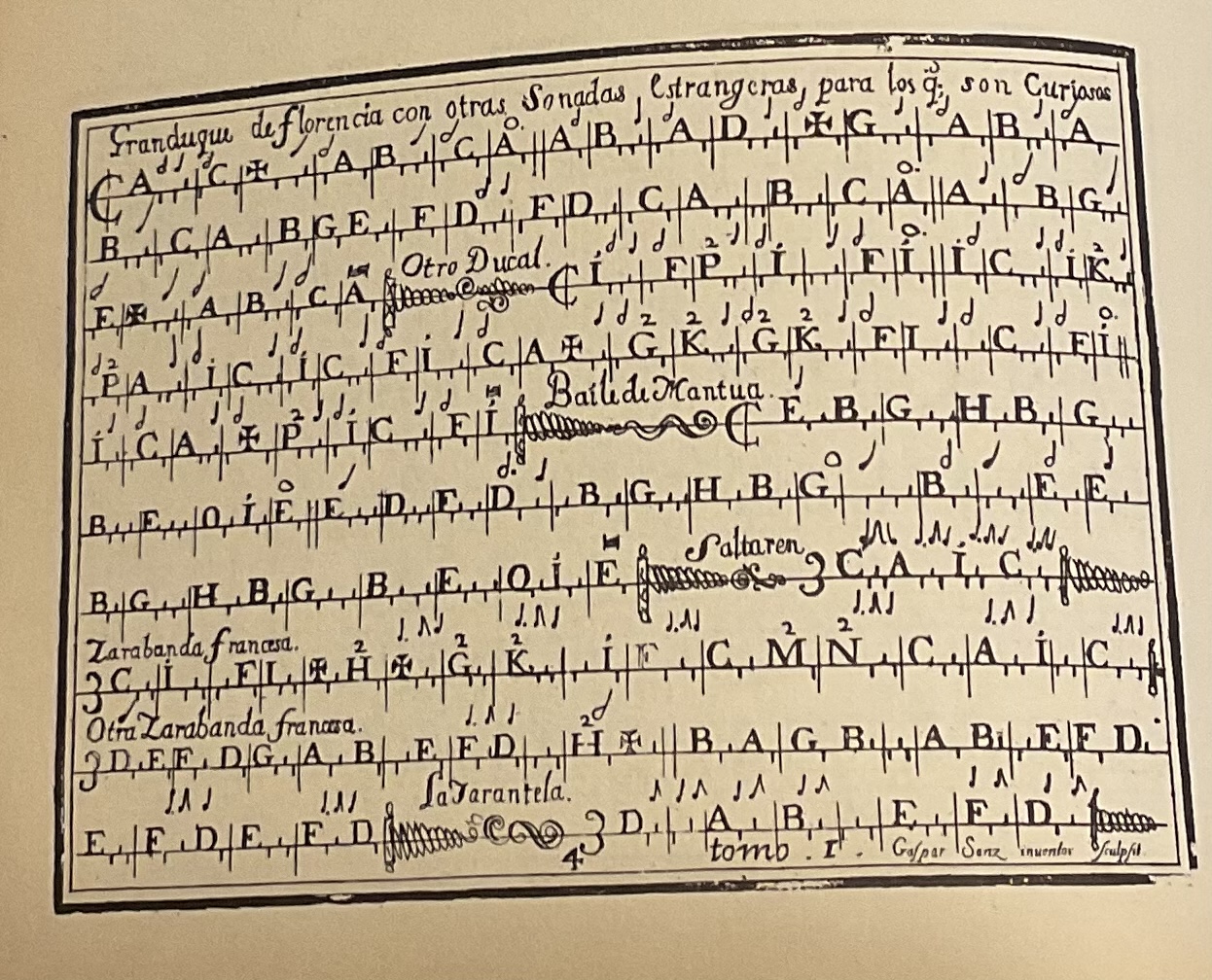

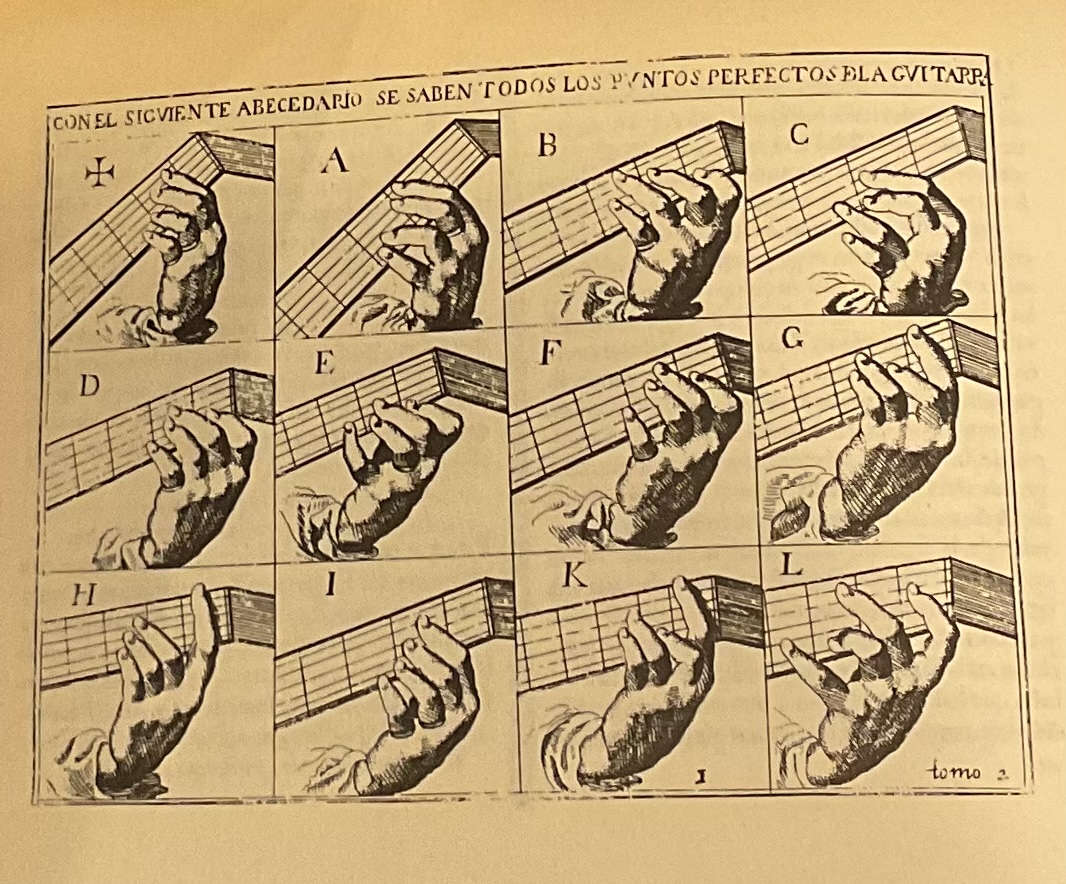

Ok so I don’t understand the one you mention. The Jacaras does move on weak beats, but I don’t see a pattern. But I do see the Fandango concept in the Zarabanda Francesa. Here are the basic compas expressions…in particular we catch glimpses of the exact idea where the chord comes on 3 and carries over the barre line with “otra Zarabanda Francesa” (see bottom left of image). Especially in the middle there were “F D, D carry over”.

"3" as in 1-2-3 or 12-1-2-3. I think of fandangos in 12 in order to compare it with other twelve count palos and because they have their origin in ternary dances where 12, 3, 6, and 9, are metrically strong.

THe only thing I would question is whether or not Sanz intended that as a cycle or, since this is an improvisation tradition, if that was one of many gestures, or phrasings, a guitarist could add to his vocabulary.

Waiting for Estebanana to enlighten us because none of us have grown or learned anything new, or modified our views.

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 3 2023 18:50:56

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito)

|

|

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: Romerito

quote:

Sorry I did. I simply wanted to know if there are more pieces in the repertoire that utilize the same tonality and final cadence that your Baxo Contrapunto uses.

Is that in the "eighth tone?" I have not researched Narvaez as much but I did a deep dive into modal theory. It is a very confusing topic. All I can say is that the eighth tone (if that is what you were looking at) does not sound to my ear like flamenco, at least not the phrygian based palos. The tono 3 and tono 4 (of the tonos de organo, NOT MODES) are closer with 4 being a "mi" mode, that is, closer to flamenco phrygian tonality.

I do wonder why the tuning disappears in the Spanish and Italian Baroque guitarists. How would it have endured into the 20th century but not ever get used by anyone else? That seems improbable.

Modal theory confusing Correct! As Early music sources video shows, the theories are quite individualistic and all over the place. As modern folk we can sort of interpret what they are doing based on the concept of 4 modes and their relative plagal modes. So, D dorian and then D Aeolian, from G dorian relation are 1 and 2. Yes 3 is E Phrygian proper and 4 is like half cadence from A minor, so harmonic minor with emphasis on the dominant, but you can see how vague that is then. Keep this in mind because the approach to the E in both cases might be the same (Dm/F-E) rather than what you would THINK is a rule being Am-E should be what is done for tono 4 for distinguish. The wishy washy relationship is a major important reason why modes 1,2,3 and 4, all get lumped into “minor keys”. Next are the vague lydian and hypo lydian, 5 and 6. Due to ficta notes employed leisurely, it is rare we hear any “Lydian’ anything in those pieces but for on occasional passing #4 on the way up. Since plagal would be good ol’ major, both modes always sound like basic major key operations to our modern ear. The 7 and 8 mixolydian same deal. So the 5,6,7,8 collapse into “Major keys” during common practice period. But that brings us to the piece in question.

So I tried to explain before, it functions as G Mixo for the most part, using the same ficta sharps as mode 5 or 6 would, F#, however the plagal would be D mixo, which he only uses briefly, and even we see/hear a Bb. Now, that darn Bb I suspect is a typo in the original. Why? Because he sets up this figure “#7-1-2” and the anticipated major 3rd degree is always there either in “chord” or scale run…but then he transports the figure to the 5th or plagal below tonic, and we hear this bizarre flat 3, as if he is transporting this figure to a minor mode. I personally feel you can alter that 1st fret note to the second fret and it works better in the context of the entire piece.

Anyway we soon see a proper appearance of that flat 3, however transported to the key center a 4th above (implying that the starting G mixo mode has moved to C Mixo relatively speaking). And the relative minor of THAT takes over the rest of the piece, which is not typical. Based on concept that G is mode 8 plagal of C, then A minor means he has abandoned the tono 8 concept and is in the relative mode 4, which as expected, eventually resolves to E Phrygian, however via Dm-E like tono 3. Griffiths admitted to me that this was unusual, though not breaking any rules. So simply put it starts in the relative mixolydian then resolves relative Phrygian, and taking into account the ficta notes F# and Bb, this is exactly what our toque Levantes do all the time, mimicking the cante which forces these harmonies on the guitarist TRYING to make it work like a simple fandango.

My interest in this piece, however, was that all the above modal gobbledygook is TRANSPOSED DOWN A MINOR THIRD from the conception of ecclesiastical solmization or church modes, putting the G mode into the CONCEPTUAL KEY of E mixo, that explores A major before moving to F#m, finally cadencing on C#. All this coupled with the fingerings that result from the TUNING of the instrument is what I was hopping to find more examples of. Griffiths says I will NOT find it, or that he does not know about any others. His tono 8 Fantasia is close, and does briefly have the figure I was looking for (A-G#-E-F#-C#-D, then again ending F#-D-C#, which Montoya inspired Paco and Tomatito to include in their versions), however, is a proper tono 8 throughout sounding like A major that eventually ends on E as I described the plagal mode should do. But absent are the G naturals and C# Phrygian resolution that gives the other piece the “Rondeña” flavor.

About the tuning disappearing, I don’t think that is what is going on. As Bermudo explains, vihuela IS A GUITAR with a string added below AND ABOVE (imagine capo 5). So the guitar only adds a string ABOVE (bass string I mean) in the Baroque, that is all. Not that people should fiddle with the internal tuning of the instrument. The problem for us modern minded folk is about absolute pitch, was NOT in their minds back then. They literally have a new instrument built if they needed a lower or higher tessitura. That is why today, you see all these nerds on YouTube playing old guitar music on their ukuleles

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 4 2023 17:29:55

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Romerito)

|

|

|

quote:

THe only thing I would question is whether or not Sanz intended that as a cycle

No need…the pieces prove it literally. And I don’t think it is HIS intention, rather the phrasing of the form requires it obviously. I don’t know shyt about Zarabanda unfortunately, nor why the Francesa one is so special in this regard, but I absolutely see the relationship to our fandango. Something to look into further?

Notice in the piece (not the rasgueado chart) how every 6 counts there is a resolution on the 3rd count (rather than the downbeat). That is EXACTLY what fandango does, and you can use 12 but that is “cuadrao” and internally the half phrases are permitted and used. (See the end of my Paco tutorial 7 where I explain how to disrupt the 12 count). I count differently if using 12s than Solea, because the 10 count phrase does not “map” to the fandango. I point out in the Paco tutorial the phrase that is important is 5-9. Perhaps that maps to your 12 as 6-10, which you might think is the same but it really isn’t. And it means the conceptual start is count 2 which for me is weird. But if you are starting that on 12, then the IMPORTANT resolution maps as 4-8, which is just even worse IMO. The safe thing is to mentally separate the two 12count concepts (same for siguiriyas).

quote:

Waiting for Estebanana to enlighten us because none of us have grown or learned anything new, or modified our views.

Speak for yourself. Notice how I kept my mouth shut and asked questions years ago when you guys had this one going. I genuinely learned a lot here. However since resurrecting this thing (sorry) a lot of my learning was done off line (my own observations and the info from Mr. Griffiths). And related in another thread Estebanan provided Bermudo (which I have already checked through the entire collection). In fact I found in Bermudo a great example of vocal polyphony and why “chords” are a problematic description, I intended to share here but I guess I would be preaching to the choir? Unless a new voice comes on and wants to see it I will keep it to myself.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 4 2023 17:44:26

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to estebanana) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to estebanana)

|

|

|

quote:

Who is the genius that resurrected this necro thread?

I had a pretty simple question. Nobody had a clear answer for me (is there MORE like Baxo tonality stuff in the Vihuela rep in general was the question, without me having to look for it). So, I went digging myself. Like I suspected there is more. Fuenllana has a series of pieces called “Strambotes a cinco”, with chordal accompaniment (in this case, very block chord style by comparison to the polyphonic style we have discussed) with lyrics underneath. I have no clue just yet, what a good definition is of these canciones exactly (again, if anybody knows?), however, several are in F# minor and at least one has the C# Phrygian approached as a half cadence….so not as nice as Baxo, but the tonality is there. Also the special voicing with the G# in the top voice is present. That is almost MORE specific than the Baxo piece, except Baxo has the open string scalar sequences that Montoya uses at times.

As an added bonus, and I suspected I would find this in there also, one of the them is in the key of D major, and sure enough we see the big open Rondeña D chords ringing out because in addition to the lute tuning of F# open, he also tells us to drop D. Of course, the G natural vs. G# affects the final results, but, taken TOGETHER as a set, I have found a nice little package from a general source that suggests Montoya was influenced by SOMEONE playing this stuff with specific tuning and tonalities.

To recap, I am seeing specific possible sources of Inspiration for Montoya’s Rondeña from these pieces:

Narvaez: Fantasia de Octavo tono (book 1), Baxo de Contrapunto (book 6 last piece),

Fuenllana: Strambotes a cinco, two in F#m, one in drop D (actual tuning Montoya uses, folio cxiiii). Also a Kyrie of Josquin in F#m is in the collection that ends on C# (folio xciii).

I will add to this short list if I discover more.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 13 2023 16:28:48

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Richard Jernigan) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to Richard Jernigan)

|

|

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: Richard Jernigan

quote:

ORIGINAL: Ricardo

I have found a nice little package from a general source that suggests Montoya was influenced by SOMEONE playing this stuff with specific tuning and tonalities.

Interesting parallels, but could it be due to something akin to "convergent evolution?"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convergent_evolution

I'm not even suggesting that this is the case, just mentioning a possibility.

RNJ

Yes I have been thinking about that type of thing too. As you can see, there is a question in the biological case, whether the analogous morphology is a result of adaptation to the environment or not…in that sense is this type of similarity inevitable? Interesting to think about with hypothetical alien life morphology. In music similarity, what I was thinking about was that I had come up with a falseta and years later I see this guy chicuelo with the same guitar and goatee as myself playing a very similar idea. And I thought at the time “everybody is gonna think I am copying this guy”, knowing full well there was absolutely no direct connection. However, it is at the same time not “coincidental” that this occurred. As we look backward, we see two guys inspired by the same individual pieces, following the guidelines of FORMAL STRUCTURE, and then the instrument itself is part of the equation (brand and model). The only true surface similarity was the goatee.  But all the rest actually has a deeper connection and points to a source of inspiration. Applying this to Montoya I feel a similar thing where something deeper is connecting these two supposedly unrelated genres. It is either a physical direct link (between 1912 and 1927, Montoya saw this music executed with his own eyes), or some historic lineage (gitanos have preserved these tonal structures with the guitar via oral tradition, hence it is unrecorded/untraceable). The idea it is pure coincidence is also possible, however, just like the biological cases, when there is so much similarity it begs one of a variety of causal connections (genetic, environmental, etc.). But all the rest actually has a deeper connection and points to a source of inspiration. Applying this to Montoya I feel a similar thing where something deeper is connecting these two supposedly unrelated genres. It is either a physical direct link (between 1912 and 1927, Montoya saw this music executed with his own eyes), or some historic lineage (gitanos have preserved these tonal structures with the guitar via oral tradition, hence it is unrecorded/untraceable). The idea it is pure coincidence is also possible, however, just like the biological cases, when there is so much similarity it begs one of a variety of causal connections (genetic, environmental, etc.).

One thing I can tell now is that statistically, I am not seeing enough typical thing (yet, having only examined Narvaez, Fuenllana, Mudarra, Bermudo, Venegas partially) to call this coincidence “noise”. For example, E minor guitar licks that resemble Granaina is just noise to me, even in very specific lines or chords…there is simply TOO much material out there that this HAS to occur by the nature of the instrument and statistics. Frankly, it is surprising to NOT see more Drop D in the Vihuela music than ONE piece. But I am still looking. Thankfully there are only 9 publications (7 plus Bermudo and Venegas). Again, any more stuff is welcome by folks that are more familiar with this repertoire than myself.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Mar. 14 2023 11:22:45

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14822

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to estebanana) RE: Great Grand Daddy of Flamenco (in reply to estebanana)

|

|

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: estebanana

Who is the genius that resurrected this necro thread?

Now I have to read it and fix a bunch of stupid ideas.

quote:

In standard lute tuning of that time a lute in G at 600mm scale would be GCFADG - like guitar tuning intervals but with the third string one step lower-

It’s possible a bigger instrument in lute tuning existed, the bass lute was usually in D with about a 665 mm scale tuned like a guitar with the third string a step lower. So this brings up the possibility of a lute in E maybe around 650 mm scale- then tune the bass E string down one whole step and you are in modern guitar Rondena tuning.

Most of the vihuela music was written for the instrument in G with the 600 mm scale, so on that one tune the bass G to F and you’re in a Rondena tuning with the cejilla on the third fret on a modern guitar

Did you follow that?

But yeah Fuellana was cool and I’m sure he used different tunings.

Short story, all they had to do is drop the lowest string one step while in common lute tuning and it’s a version of Rondena tuning

Sorry, grabbed this quote and transported to this relevant location. I get what you are saying about instrument construction and pitch class…however, the pitch issue, and subsequent “translation” into modern musical note names (vs ignoring pitch and utilizing conceptual tonalities like we do in flamenco with capo making pitches arbitrary), is extremely cumbersome when trying to discuss deeper musical aspects at work. For example, saying “most lutes/vihuelas are in G”, makes no sense to me, neither conceptual key wise nor pitch frequency wise. It is yet another unnecessary translation I need to make to get at a quite simple musical concept. For example, a piece for vocal by Mudarra is in alto clef, key of A minor. The Vihuela is in Gm implying the instrument is tuned in F#, or the singer has to push it up to Bb minor. Considering modern A=440z, and ancient A=something lower than 440hz (an A was really sounding like G or G# or even lower, we can’t ever know), then Mudarra’s vihuela was getting closer to modern guitar pitch after all. Bermudo gives us the 7 vihuelas, and despite the supposed “common” one in G, decides to use one tuned in A for his example. The 7 string one is tuned to G, with outrageous scordatura on the trebles going on. Considering the range of vocal music, the E tuned vihuela makes the most sense as a basis to describe ALL the music. Even Luis Venegas equates that tuning to the proper tessatura for the vocal parts (5th-baritone, 4th-tenor, 3rd-alto, 2nd and 1st soprano), so in terms of CONCEPTUAL KEY, historians should always be using the “Elami” vihuela. It is annoying to refer to any of the other 7, or let them get in the way of musical discussions. I understand that many of the scholars might be “transpositionally challenged”, as in, a modern Bb horn you talk about them playing in C major for clarity and simplicity. This business of the common lute was in G, is like constantly transposing all kinds of horn music to “Bb”, especially when we are discussing technical things like fingerings, etc.

So after that rant, the new info is in addition to the single Strambote (which I learned are Italian madrigals, and the one of Fuenllana is by Festa), Fuenllana also composed a set of 4 Fantasias in exactly the Rondeña tuning (capo 3 or so if panties are getting bunched up). The problem is like the strambote, the tonality is not Lydian, but freaking HIPOLYDIAN….or basically modern Ionian/major key stuff. So technically speaking, too many G naturals compared to our flamenco Rondeña. There are plenty of brief passages, taken out of context, move to A major via passing G#’s that, on paper, LOOK very much like our Rondeña stuff. Again, taken together with the other material in the collection in C# phrygian, and the relative scarcity of the drop D situation (it would make sense to find a lot more, yet is found in similar small percentage as Rondeña is to other palos), I personally feel it is too much to be a pure random coincidence. I feel Montoya either was exposed to this by a classical guitarist or lute player, as discussed earlier, or carrying a traditional thing that he happened to be the first to record. But I am still looking slowly through this stuff.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date May 25 2023 19:26:40

|

|

New Messages New Messages |

No New Messages No New Messages |

Hot Topic w/ New Messages Hot Topic w/ New Messages |

Hot Topic w/o New Messages Hot Topic w/o New Messages |

Locked w/ New Messages Locked w/ New Messages |

Locked w/o New Messages Locked w/o New Messages |

|

Post New Thread

Post New Thread

Reply to Message

Reply to Message

Post New Poll

Post New Poll

Submit Vote

Submit Vote

Delete My Own Post

Delete My Own Post

Delete My Own Thread

Delete My Own Thread

Rate Posts

Rate Posts

|

|

|

Forum Software powered by ASP Playground Advanced Edition 2.0.5

Copyright © 2000 - 2003 ASPPlayground.NET |

0.09375 secs.

|

Printable Version

Printable Version

New Messages

New Messages No New Messages

No New Messages Hot Topic w/ New Messages

Hot Topic w/ New Messages Hot Topic w/o New Messages

Hot Topic w/o New Messages Locked w/ New Messages

Locked w/ New Messages Locked w/o New Messages

Locked w/o New Messages Post New Thread

Post New Thread