|

Richard Jernigan -> RE: Flamenco in music conservatories? (Aug. 16 2016 3:31:00)

|

I recently received this informative message from the well know luthier and flamenco guitarist Richard Brune, and posted it in the wrong thread. Here it is in the right thread:

"Hi Richard, I was following the foro thread on flamenco taught in the conservatory, and thought I would pass this along for what its worth. As you know, Segovia stated one of his life goals was to place the guitar into universities and conservatories on an equal basis as the violin or piano, the implied corollary being that it wasn't present in those teaching situations. However, if you read Domingo Prat's 1934 Diccionario de Guitarristas y Guitarreros, you will find that there were many academic institutions in Spain during Segovia's youth (and even well before) in which the guitar was part of the curriculum. In South America it was even a bigger deal in the Rio de la Plata area, with MANY conservatories, "escuelas" and "academias" run by players such as Prat, Sagueras, Sinópoli, etc catering to the creme de la creme of society folks, especially their daughters who comprised easily 50% of the population of guitarists. Segovia lived for several years in Montevideo, so he was well aware of this activity. This applies to guitarists who are literate, since reading music was an implied requisite to entering any of these institutions.

However, the discussion on the Foro relates to flamenco, with (I think) the implied assumption that "flamenco" and "classical" players have ALWAYS been two separate entities. This was not in fact, the case, some players were literate and ALSO played flamenco, some only played written composed music, and same were plain old illiterate flamenco tocaors. This whole notion of the "Classical Guitar" being a separate art and instrument really evolved after WW II, mainly due to Segovia's desire to separate himself from other competing players who billed themselves as "Spanish" guitarists.

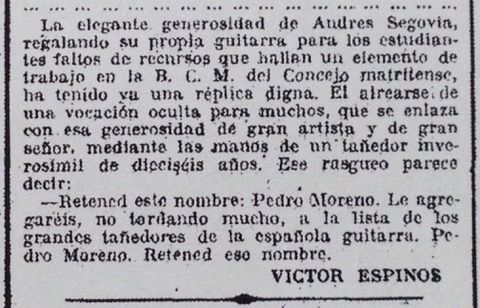

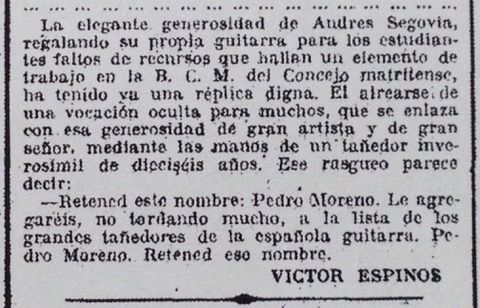

Looking at the historical record, apart from the well documented academies in South America where the guitar was definitely on an equal if not GREATER social footing than the violin or piano, its clear that the guitar in Spain also was already in formal institutions of higher learning as illustrated by these attachments. The one brief paragraph mentioning Segovia's gift of his "personal guitar" (the 1924 Santos Hernandez now in the Circulating Music Library of Madrid) comes from the June 4, 1932 edition of "La Epoca," and was part of a review of Pedro Moreno, who played a concert of "Soleares, Siguiriyas, fandanguillos, Tarantas, in addition to transcriptions of Zarzuelas..." The full review occupied nearly a full column of the newspaper page!

The advertisement for the Sevillian guitar maker Manuel Soto y Solares comes from the 1876 edition of the "Guia de Sevilla," which was kind of like an atlas/phone book and general informational compendium for residents and businesses in Sevilla (sans phone numbers of course, since they had not yet been invented). As you can see, Manuel Soto y Solares, who only made the heavily domed "Tablao" style instruments used ubiquitously at that time in flamenco tablaos, is aiming his products at "Professors and aficionados..." I might also add that this was the same street Antonio de Torres worked on when he lived in Sevilla, and there was also a 3rd maker on the same street, Manuel Gutierrez, (who was was gone by 1876, as was Torres, who had moved back to to his hometown of Almeria around 1869). Torres had business relationships with both of these makers, when the 3 worked on the same street. Torres' personal model was created by "borrowing" design ideas from these other two makers, who were already established in Sevilla when Torres arrived there.

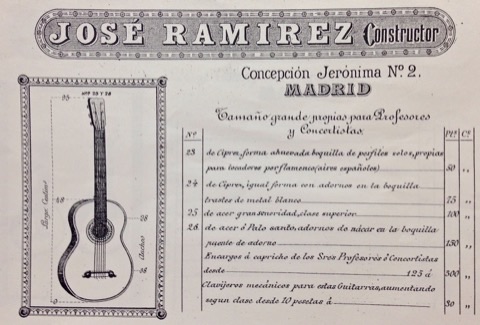

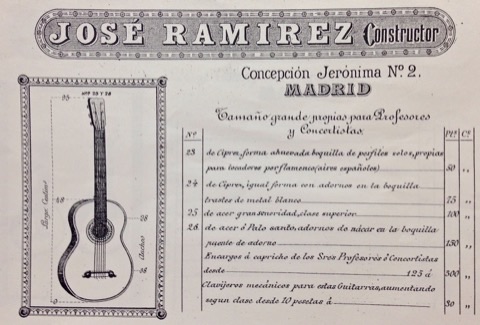

And then there is the catalog of José Ramirez I in which his most expensive custom models are intended for "professors and concert artists." Note that nowhere in any of this is to be found the term "Classical Guitar." José I also made only domed ("ahuevada") tablao style guitars. And of course, there has already been extensive discussion on the foro regarding the Rafael Marín "Metodo" which is of course written in both cifra and musical notation, a book I think was aimed primarily at non-gypsy aficionados. It appeared around the same time that recordings were first being sold, making flamenco music accessible and (most importantly, repeatable) for those trying to learn by ear who were not born into the art.

In the end, I would concur with Richard Marlow, one doesn't learn "salero," "gracia," y saber como "ser y estar" in an academic setting, but one does learn technique, history (if that's important to you...), and basic structure from this kind of setting, so these are useful sources for those not born into the art. Traditionally through the 19th century, being born into the art was the only way to learn flamenco, as this was nearly 100% dominated by a handful of gypsy families, whose descendants today are still among the most creative and vital fountains of original creation in the art. By the way, Silverio Franconetti is the ONLY "cantador de Cante" I have found in the 1876 guia de Sevilla. Gypsies are excluded from inclusion. Like the art of flamenco in relation to the history of the modern guitar, they were written out of the history books that would have documented their professions and domiciles.

Best wishes, Richard"

Images are resized automatically to a maximum width of 800px

|

|

|

|