|

Pimientito -> RE: Give us your opinion: Advent of the six-string guitar in flamenco (Feb. 2 2010 0:00:33)

|

That was interesting Romerito. The relationship between the classical and flamenco players is quite convoluted. They obviously influenced each other in the early 1800s

[from: Guitar and Lute, March 1983]

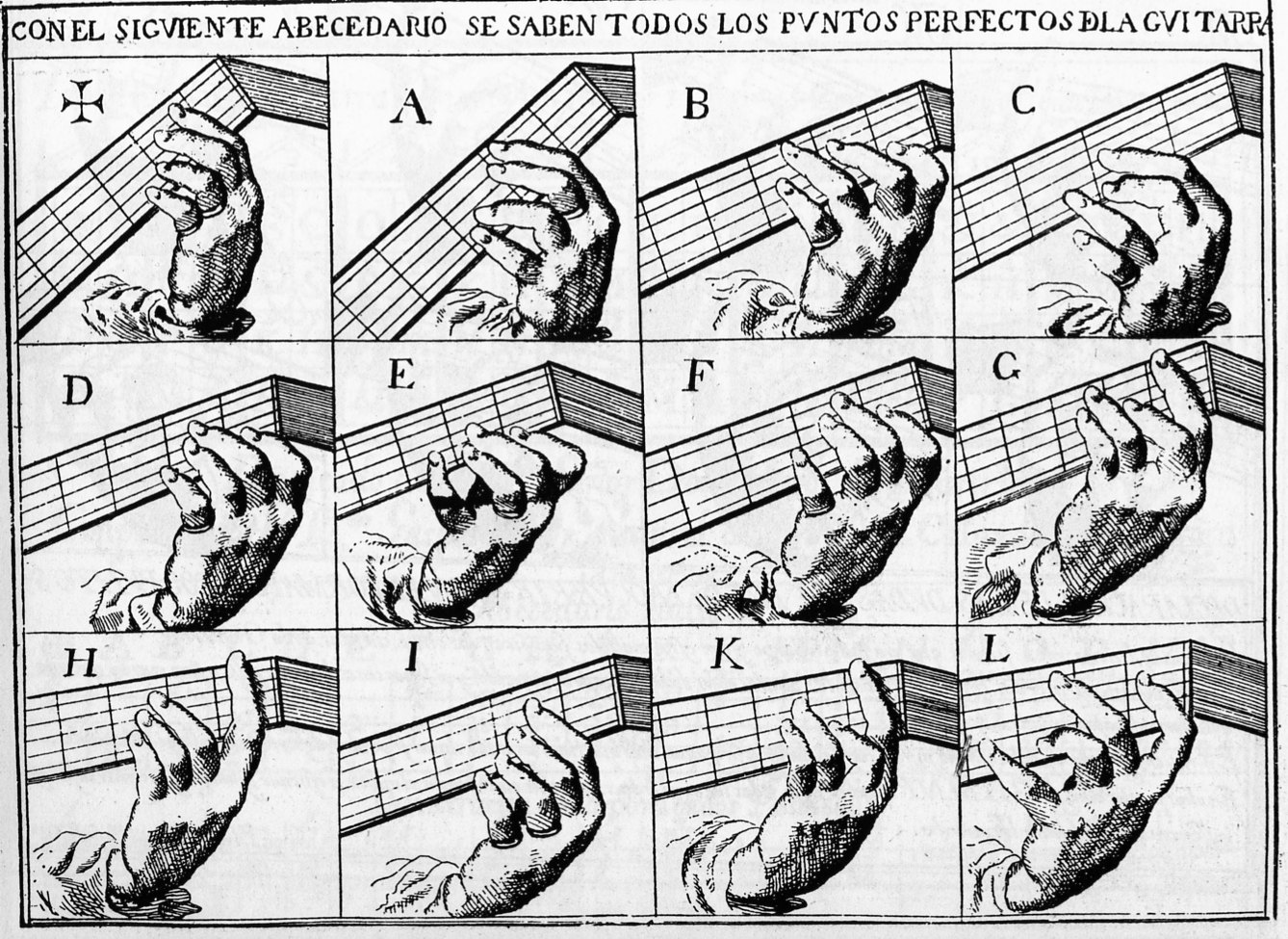

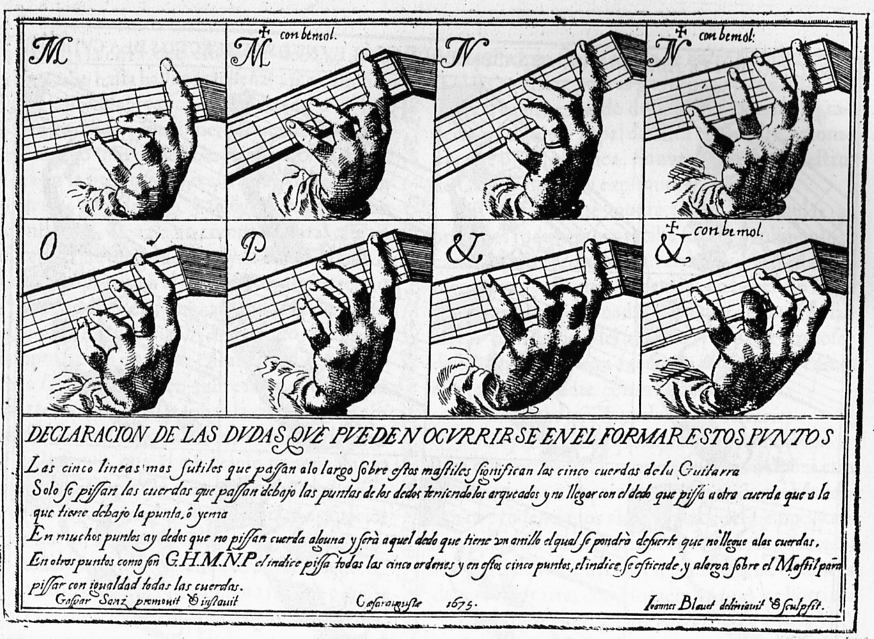

"By 1700, the guitar had acquired a sixth string and was played in two

different styles. As a plucked instrument, it had been highly developet

for playing what we now call "classical" music, the music of the

nobility. The popular instrument of the people was played using

rasgueados (strumming with the fingers). While these instruments were an

integral part of Andalucian folk music, it is generally held that they

did not play much of a part in the early development of gypsy music.

Also by 1700, both Andalucian and gypsy music had - acquired

recognizable forms, and references to them began to appear more

frequently in the literature of Spain and other countries. Although

gypsy music was still very private, a ritual of the gypsy families,

gypsies had become a popular theme for theatre works and wete witely

mentionet. The -oldest written example of flamenco is a siguiriya found

in an eighteenth century Italian opera,"La Maschera Fortunata by Neri.

In 1779, Henry Swinburne wrote in Spain in the Years 1775 and 1776 that

the gypsies of Cadiz danced an indecent dance called the manguidoy to

the rhythm of hand- clapping; he also mentioned guitars, castanets, and

rough- voiced singing of polo. Other references speak of the taconeo

(heelwork) ant the seguitillas gitanas. (The seguidillas were live}y

songs, related to the sevillanas, not the profound gypsy cante of today

that has a similar name.) By 1800, references indicate 24 dances that

were supposedly performed by gypsies; most of those no longer exit, and

none of them are specifically part of the gypsy dance we know today,

although some survived in the non- gypsy flamenco, particularly the

fandangos and the segui- dillas (sevillanas).......

....The music that was accesible to the traveler in this period was almost

certainly dominated by the Andalucian element rather than the gypsy.

Gypsies may have performed for the public under certain circumstances,

but reports do not seem to indicate that they were performing what would

appear a few decades later as the highly developed cante gitano (forms

like the tonas, siguiriyas, and soleares). It is important to keep in

mind the differences between these two forms of music, for these

subdivisions of flamenco still exist today. The gypsy cante was private,

emotional and very personal; it used primarily the phrygian mode and

complex rhythm patterns, and was very difficult to sing; the

accompaniment was most often the rhythm of handclapping, fingersnapping,

knuckle-rapping, or the tapping of a cane - even today some forms are

always sung a palo seco (a capella); even when the guitar began to play

a more important role in flamenco, distinct gypsy and non-gypsy styles

of playing emerged. Andalucian folk music, on the other hand, was very

public music, sung in the major and minor modes and using 214, 314, or

6|8 meter; it was often accompanied by groups of instruments.

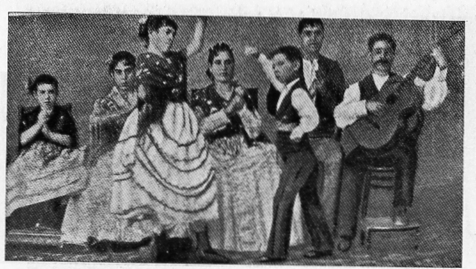

In 1842, events occurred that would change the nature of flamenco and

gave birth to what we now refer to as the "Golden Age of Flamenco."

Certain Andalucian taverns where flamenco was cultivated began to place

more emphasis on the performance of the cante and baile (dance). The

performers were usually not professionals, but performed out of aficion,

love of their art. On the rare occasion that a guitar was available, it

might have been strummed in an improvisational manner, but the guitar

had not yet emerged as an integral part of flamenco. However, there must

have been some guitarists starting to develop the flamenco style, for it

would be in widespread use within a few decade. Moreover, the Russian

composer Glinka was entranced by the playing of the gypsy guitarist El

Murciano in Granada, and he wrote down some of the guitarist's

compositions. In neighborhood patios, country inns, and tiny taverns,

flamenco made its first public appearance and began its emergence from

the private, almost religious position it had held in the gypsy families.

The earliest known cafe de cante, as the first flamenco

nightclub were called opened in Seville in 1842. For the

first time flamenco artists were paid on a regular basis.......

......In the cafe cantante, the guitar became an important part of the

flamenco "show", and guitarists developed rapidly, learning from and

competing with each other. They competed not only with each other, but

also with the dancers and singers. To get attention, guitarists began to

insert more falsetas (melodies) into their playing, taking their themes

from the cante. Soon, each club had a soloist, some of whom resorted to

playing behind their backs, over their heads, or with gloves. An early

soloist, Paco Lucena (c. 1855- 1930), is credited with introducing

picado (rapid melodic passages played with the index and middle fingers),

three- fingered arpeggios, and tremelo that he learned from a classical

guitarist. Another great guitarist, Javier Molina, was more of an

accompanist, but he helped to mold two of the founders of the modern

flamenco guitar, Ramon Montoya and Nino Ricardo....

.......The guitar blossomed during this time. At the forefront was Ramon

Montoya (c. 1880-1949), a gypsy who lived most of his life in Madrid and

greatly influenced all guitarists who came after him; both Sabicas and

Mario Escudero played a great deal of Montoya's music on their early

records. He developed his style while playing for singers in the cafes

cantantes, and later, influenced by the playing of the classical

guitarists Francisco Tarrega and Miguel Llobet, he began to incorporate

classical techniques into his playing Montoya is credited with creating

the four-fingered tremolo now used in flamenco and with introducing more

complex arpeggios and picados (single note passages); he also developed

the left hand for playing his many difficult creations. Montoya composed

many melodies that are now considered standard or "traditional" and

was the creator of a flamenco form, the rondeña for guitar, that is now

part of the standard repertoire. Montoya alternated between accompanying

the great singers in private parties, recording with most of the top

artists, and giving solo recitals around the 3 world. He also recorded

some guitar duets with Amalio Cuenca, a soloist who had been one of the

judges in the Granada contest.

Other guitarists included Niño Ricardo, one of the greatest influences

on flamenco guitar between Ramon Montoya and the moderns. Ricardo made a

living playing with orchestras and operatic singers, but on the side

he created profound flamenco music. There was also Manolo Badajoz, who

preferred private parties to theatrical performances, Miguel Borrull,

Luis Yance, Luis Marvilla, Esteban Sanlucar, whose flamenco compositions

are still played by concert artists, and even Melchor de Marchena, who

was quite a virtuoSo in his youth, but then became the exemplary subdued

and emotional accompanist in his later years - from the 1950's into the

1970's.

The great guitarist, Agustin Castellon "Sabicas" brought the music of

Ramon Montoya to the Americas and, probably as a result of his long

association with the gypsy dancer Carmen Amaya, developed a strongly

rhythmic style, in contrast to I Ramon Montoya's more free and Iyrical

approach. In the 1940s and 1950s Sabicas added many new forms to the

solo guitar repertoire that had previously only been sung or danced,

including verdiales, zambra, garrotín, sevillanas, colombianas,

milongas and guajiras."

|

|

|

|