Welcome to one of the most active flamenco sites on the Internet. Guests can read most posts but if you want to participate click here to register.

This site is dedicated to the memory of Paco de Lucía, Ron Mitchell, Guy Williams, Linda Elvira, Philip John Lee, Craig Eros, Ben Woods, David Serva and Tom Blackshear who went ahead of us.

We receive 12,200 visitors a month from 200 countries and 1.7 million page impressions a year. To advertise on this site please contact us.

|

|

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 - 1881

|

You are logged in as Guest

|

|

Users viewing this topic: none

|

|

Login  | |

|

kitarist

Posts: 1715

Joined: Dec. 4 2012

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

And I found another book from 1838 about travels in Spain that I had missed before, so will post from it in this post.

Written by Italian-born Carlo/Carlos/Charles Dembowski (1808-1853), it is called "Two years in Spain and Portugal 1838-1840", published in 1841 in French.

Charles Dembowski was the older brother of astronomer Hercules Dembowski (who has a crater on the Moon named after him). Their parents were Jan Dembowski, a Polish Napoleonic general, and Italian Matilde Viscontini who later became French writer Stendhal's muse.

Here are some interesting excerpts from his trips in 1938 to various cities – Granada, Sevilla, Cadiz, Manzanares, Malaga. In Manzanares he describes in detail the dancing and accompaniment (including guitar work) of manchega which he calls a type of fandango. In Sevilla he mentions Triana and gitanos in a nice scene of festive mood. In Cadiz he advises his reader to not overlook going to the gitano quarters to hear them playing a Playera. In Granada he gives some history about fandango and names several popular dances. In Malaga he describes in great detail what seems to be a flamenco or flamenco-adjacent juerga. While only the Malaga excerpt and the Cadiz mention may be of any relevance to flamenco (as the rest I think involves folk dances and non-gitanos), I excerpt all of it below for general interest as well as in case someone like Ricardo with his detailed musical and musically-informed historical knowledge about flamenco can pick up on something else that is actually relevant.

Excerpts follow below; free access to the complete text in French here:

https://archive.org/details/deuxansenespagn00dembgoog/page/n6/mode/2up

pp. 137-139: (Manzanares, Jul 1838)

“Manchega is a kind of fandango, but much more lively than the original fandango. It has three parts, and this is how we dance and sing it at the same time. The dancers being arranged in pairs in two lines facing each other, the guitarists scrape a rich arpeggio in A, which serves as a prelude to the song, then they hum in a low voice the first line of the verse they propose to sing: it often happens to them to repeat it in the same way during the first four bars of the tune. Then silence of the voice, and three new bars of scraping on the guitars. As soon as the fourth begins, they sing the verse of which they had hummed the first line. Here the castanets are heard and a lively dance, a curious mixture of fandango steps, the jota and noisy taconéos (double heel kicks), begins between the lady and the rider of each couple. The dance continues for nine bars, the last of which marks the end of the first part of the manchega.

“After which the guitarists scrape a new arpeggio, which continues until each pair of dancers has changed places with the couple facing them, which ladies and riders perform, without ever touching their hands, by means of a walk filled with gravity, which contrasts very singularly with the mad gaiety that everyone displayed a moment ago. When all the couples are established in their new places, the songs resume, and with them, for nine more bars, the taconéos and the expressive and passionate poses. This second part completed, the couples return to the old square.

“The third part of the manchega is performed like the first, always in the midst of songs and dances, but with this additional curious peculiarity: in the middle of the ninth and last measure of the aire/song, chants, guitars, castanets, suddenly fall silent, while the dancers, for their part, stop in the position, usually very graceful, in which the sudden interruption of the music has surprised them. This silence, this general immobility, succeeding so imminently so much animation and gaiety, produces an effect the charm of which we can easily imagine. The set of poses of each pair of dancers is what is called the good parado; and each one pays particular attention to ensuring that, when the music ceases, its last pose is pleasing to the eye. As far as women are particularly concerned, they make such soft arm turns, so fast taconéos, so graceful steps, so varied, so tight, they finally take such sweet attitudes, that if they are pretty , seeing them dance we forget any kind of philosophic.”

p. 159: (Sevilla, Aug 1838)

“The gypsies are perhaps the only ones here who have gained something from the suppression of convents, because of the little kindness the monks had for them. Currently they reign supreme in the suburb of Triana, so called in honor of Emperor Trajan, who is claimed to have been born there. Nothing was more amusing these last few days than to see their good mood overflow on the occasion of the feast of Santiago, patron saint of Spain. The bridge of boats that unites their neighborhood to the city was swarming with lanterns, their streets were carpeted with lemons and oranges, and the whole suburb swam in an atmosphere of oil smoke, which rose from the donut stoves of the gitanas. I would have defied you to escape them. Two of them came to meet me with a kind smile, took my hands and said: "Ah! Que buen mozo, venga usted aca “. They dragged me to their stoves.”

p. 173: (Cadiz, Sep 1838)

“Another amusement which the traveler should not disdain here is to go in the evening to hear the gypsies sing the Playera in the quarter they occupy, between the prisons and the mud gate.”

pp.219; 225-226 : (Granada, Sep 1838)

“There is a Couplet de la Rondena, it is the Andalusian fandango, which all the ladies know by heart, and which will tell you all that Granada has preserved of old Spanish customs.

[..]

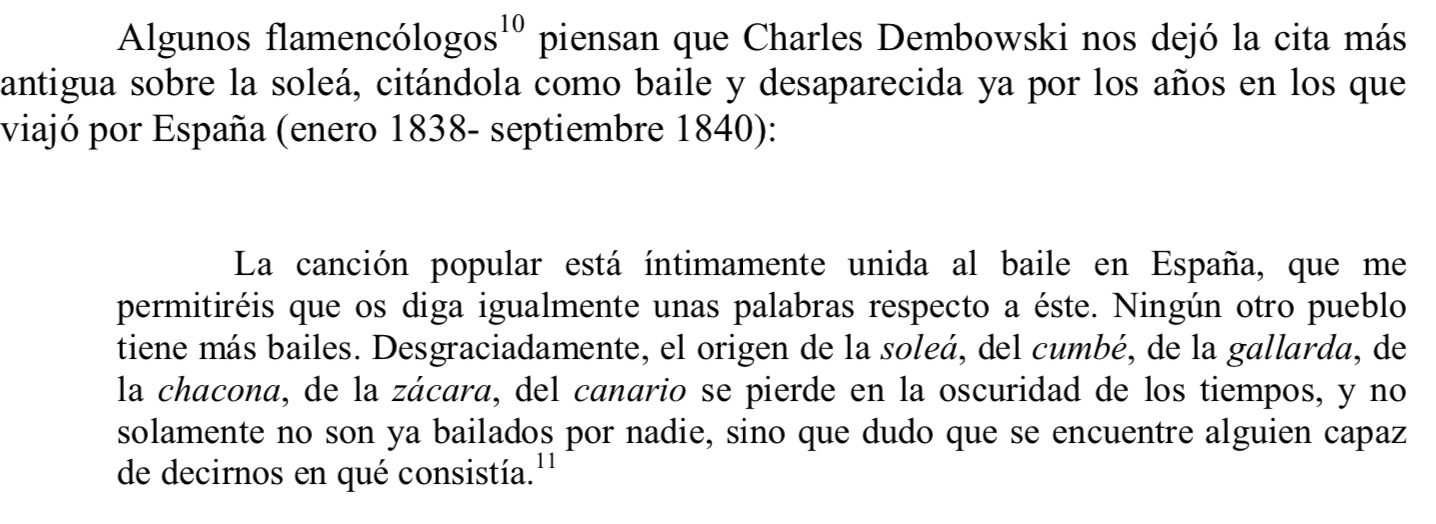

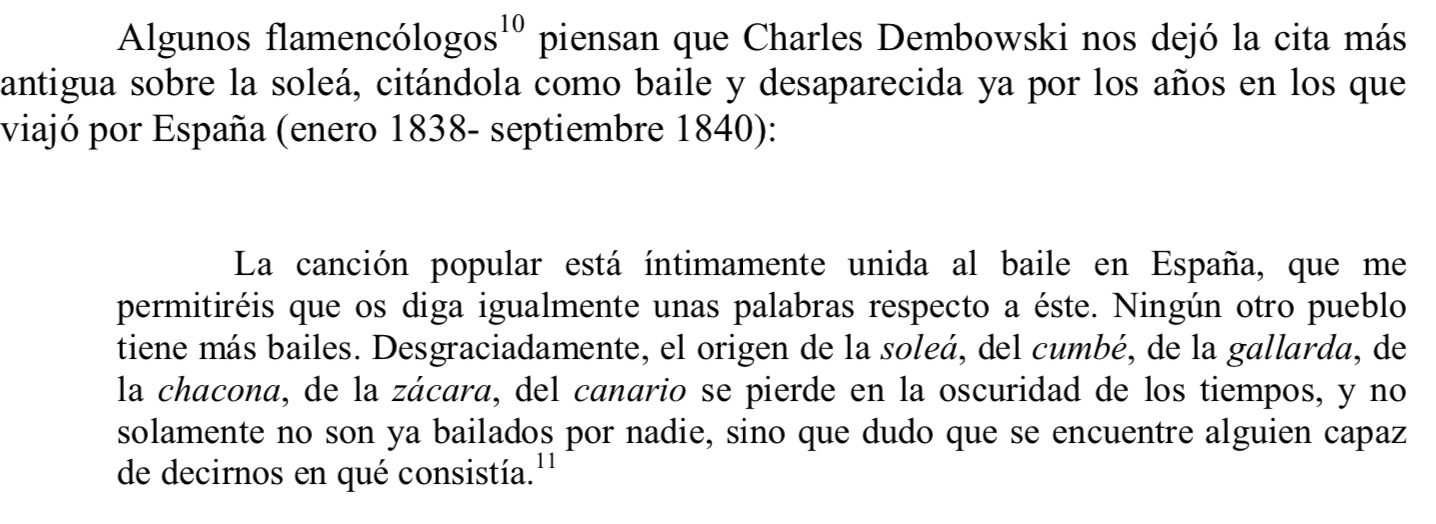

“The popular song is so intimately linked to dance in Spain that you will allow me to say a few words about it as well. No other people have had a greater number. Unfortunately the origin of folia, cumbe, gallarda, chacona, zàcara, canario, is lost in the mists of time, and not only are they no longer danced by anyone, but I even doubt that there is someone able to tell us what they consisted of.

“As for fandango, we know that it was in the spotlight in the fourteenth century. It was not, however, until 1740 that it was submitted, as well as the manchega with its fixed principles and rules, by Don Pedro de la Rosa, a monk gentleman whom the bad state of his affairs had forced to throw himself on the theater. Twenty years later, Don Sébastien Zerego invented a new dance; he danced it so lightly that it was difficult to catch the moment when his feet touched the earth. So the inhabitants of La Mancha took to saying that Don Sébastien _volaba_, was flying, and he was only called by the nickname of volero or bolero, the flying man, a name that remained in the dance itself. By extension all the dancers were then called boleros, and the dancers boleras or bolerinas.

“At the same time, in Andalusia, they danced tirana, polo, zorongo, cachirulo. The guitarists sang couplets of four verses with assonant endings, the dancers follow the phrases of these various tunes, moving their bodies early to the right, sometimes to the left, and moreover waving their handkerchiefs or their hats in front of their ladies, who, for their part, gracefully swung their aprons, in the manner of the dances of the ancient Gaditanes. Subsequently, the abuse of these gestures became such that all these dances ended up being banned from any meeting however decent. The charming melodies in which they were performed remained, however, and the famous Spanish composer, Don Vicente Martin, introduced them with immense success in the operas which he performed in the theaters of St. Petersburg, Vienna and Naples. “

pp.249-252 : (Malaga, Nov 1838)

“Yesterday, very early in the morning, the blind came to remind me by a sort of serenade that it was Saint-Charles, the feast of my glorious patron. They sang, accompanying themselves on the violin, the guitar and the Basque drum:

Los mûsicos decimos

Con alegria :

Tenga el senor don Cârlos

Su feliz dia.

Libre de danos

Que la tenga feliz

Por muchos anos.

“My fellow boarders then came to congratulate me in their turn, and to show them all my deference to Spanish customs, and at the same time satisfy my own curiosity, I offered them a gypsy ball for the evening. The procurator, a man of great thoughtfulness, immediately offered to find the gypsies for me, and they, who are continually in trouble with the law, accepted the invitation of the man at the bar as good fortune. .

“At nine o'clock in the evening, everyone having gathered in dona Mariquita's shop, in my capacity as patron of the party I gave my arm to the two most beautiful gitanas, and all the guests followed me into the room. of the ball which was lavishly lit by an old lamp with three beaks, held up to the ceiling by a piece of string.

“The gypsies, eight in number, three men and five women, took their places at the back of the room. Among the women stood out Rita by the expression of her Moorish physiognomy and the richness of a voluptuous figure free from all ties. A curl of black hair adorned with a rose fell from her left temple, and her short Indian dress left uncovered a cute foot imprisoned in a white leather pump, to make all Parisian beauties, even Chinese beauties, jealous.

“Near Rîta sat fat Joana, her mother, twice our size, and all covered with chains and chains of good and fine metals. She goes among the gitanas of Malaga for having imprisoned the devil in her home, and this belief has made the fortune of the stove of chestnuts that she maintains in Constitution Square.

“Pepe, the most successful dancer in Malaga, where he lives making false keys and holding a cabaret, wore white trousers, a red scarf, a shirt with a huge frill, and a ring hanging from his left ear. with a small hand making the horns, which reminded me of the Neapolitan jattatura.

“Rita took hold of the guitar, and the elegant abbot, Don Pedro, opened the ball by dancing a fandango with Dolores, a young worker embroiderer who works at Dona Mariquita. My abbot's pirouettes will not scandalize you, because you doubtless know that priests are not excluded from the rights of nations at Spanish balls.

“On the arrival of the tenor and the bass, who came out of the Opera where they had sung Semiramis, the songs and dances of the gypsies began. One of them accompanied by scraping the guitar the verses of the Playera, a song which the inhabitants of the beach adore, which men and women sang alternately, marking the time with a clap of the hands of a very curious effect; this is called palmoteo.

“From time to time a gypsy would dance with his gypsy. Imagine the dancing couple. Pepe and Rita are placed opposite each other, left arm on hip, right foot back, and await the end of the verse. Suddenly the bitter noise of the castanets dominates the palmoteo and the sound of the guitar; it is Pepe and Rita who dance at the same time, reproducing the same movements of arms, feet and head. This is the promenade or the first part of the Playera; Then, when Pepe rushes towards Rita, she runs away from him, annoying him, and when Rita advances, Pepe escapes her in turn. There comes a time when the gypsies resume their songs and mingle with them exclaimations which seem to intoxicate the dancers, and, strangely enough, react on the singers and the spectators themselves. “Ola jaleo! Eche usted azucar! Ande usted salada! Viva ese cuerpo! Muerte! Alma, alma! Ole! ole! ola! ” Exclamations full of verve and animation in Spanish, and which could only be translated very imperfectly into French. All the trained spectators repeat these words; Joana's loud voice dominates all the others.

“Rita's movements are those of a Bacchante, while her face is that of Pythonisse. Lightning flashes from her black eyes, which pursue the invisible god whose influence she is under; each of its members quivers and throbs with new life. The gypsy flutters around her animated by a similar fury; finally find me some words to tell you about the accidents of this pantomime filled with passions, happiness, pleasure. Everyone applauds Pepe and Rita who, drawing new strength from numerous bowls of punch and anisette, danced several times that night.

“After supper a young widow sang with great charm the gracious songs of the Tripili-tripàla, the Panadera and the Contrabandista.

“We then heard a gypsy; butcher by trade, whose father is so overweight that he is called 'The Full Moon of Malaga'. Despite rare talent on the guitar, and despite his beautiful voice, he was hateful to hear because of his horrible pronunciation. He preceded each vowel with a v, so that the words of the song came out of his mouth as disfigured as they were ridiculous. Nothing could give you an idea of the vanity of this gypsy. Knowing that I was a foreigner, he found it pleasant to constantly interrupt the verses to offer me the guitar and invite me to pretend to hear in my turn: "Ahora cantarà usted!" Now it's your turn to sing! When he took the falsetto he stiffened and waved his legs like a possessed man, and invited his neighbors with real kicks to pay him a tribute of admiration.

"The dance was still going on, when, hearing six o'clock strike in the morning at Clock of the cathedral, Dona Mariquita, who was in a great hurry to open her shop, asked us to put an end to the celebration.”

_____________________________

Konstantin

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 7 2021 20:35:03

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14797

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to devilhand) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to devilhand)

|

|

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: devilhand

Taking about Solea, this is a plausible explanation I posted last year.

quote:

Another theory says Solea doesn't mean soledad (loneliness). The olive harvest is called soleo. Gitanos used to sing the earlier version of Solea when they worked on the olive plantation. Solea was like a work song of African slaves who sang it in a group. During the olive harvest Solea was sung in a group as well. A clear contradiction to soledad.

The problem is Soleares is also used as the title, and your explanation does not account for that as well. Also the accent on á… like tonada became toná, Soledad became soledá, and later Soleá makes perfect sense.

In the end, the song title was most likely appropriated for use of naming the form, just like all the others (fandango, seguidilla, toná, polo, tiento, tango, guajiras, rumba, possibly bolerias, etc). I suspect Caña as well. Strange we don’t have a “Tirana” in our modern rep, but I also suspect that THAT might have been a working title before Andonda came along and called it Soledad instead. That or polo (which split into solea apolá/Soleá de Triana and Polo proper later).

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 10 2021 12:19:03

|

|

kitarist

Posts: 1715

Joined: Dec. 4 2012

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

Two more interesting historical bits, though likely not flamenco-related.

1604: Actas Capitulares del Ayuntamiento de Murcia, año 1604, 11 de diciembre, folio 142 vuelto:

• Juan de Melgar, danzador, is appointed a salary of 4,000 maravedis to teach dances: “seguidillas, la Caña, Contradanza española, Danza de Espadas y otras danzas nobles y bailes villanescos"

1799: La Quicaida, a poem by Gaspar María de Nava, conde de Noroña (1760-1815):

• p. 318 (Canto VII):

“Cantó la Malagueña, y Sevillana;

El Fandango de Cádiz punteado,

Con nuevo tono en cada diferencia;

La Jota bulliciosa de Valencia;

El quejumbroso Polo agitanado;

Seguidillas manchegas placenteras;

Y de Murcia las rápidas Boleras.”

_____________________________

Konstantin

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 10 2021 18:25:23

|

|

kitarist

Posts: 1715

Joined: Dec. 4 2012

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist)

|

|

|

quote:

ORIGINAL: kitarist

quote:

Also I came across some research to do with when the various forms [names?] appear first, and have to find and review it as I seem to recall they had some documentary evidence referenced.

Found the paper I was thinking of when I wrote this. Expect a followup in a day or two.

The paper I was talking about that I finally found again is by Carlos Galán Bueno, published in 2019:

Galán, C. (2019). Cuatro claves para fechar el flamenco como lenguaje creativo. Sinfonía Virtual: Revista de Música Clásica y Reflexión Musical, (36), 5.

He is a “Compositor, Pianista, Director del Grupo Cosmos 21, Catedrático de Improvisación del Real Conservatorio Superior de Música de Madrid” so I was thinking his analysis would carry more weight as he clearly has a musical education and practices in the general field.

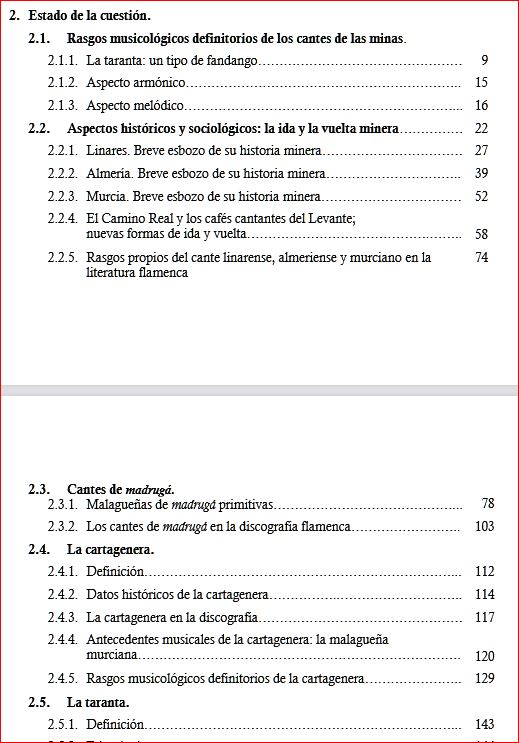

Section 6 of his paper is the one about dating the emergence of the different flamenco forms as distinctly flamenco. Apart from his own analysis in the paper, he combines and analyzes research chiefly from the recent works of Faustino Núñez and Guillermo Castro Buendía to come up with the timeline in that chapter.

Faustino Núñez I have mentioned before; he is the one who diligently went through primary sources in many archives and published what he found in “Guía comentada de música y baile preflamencos (1750-1808)” in 2008; he seems to have published subsequent finds in “El afinador de noticias”, in 2018.

Guillermo Castro is the 3000-page dissertation guy, previously mentioned here: http://www.foroflamenco.com/tm.asp?m=332747&&mpage=1&s=#332826 . He also seems to have covered everything under the sun to do with flamenco  ; publications here: http://guillermocastrobuendia.es/publicaciones.html (all his papers available for free; just not the books). A lot of them seem to deal directly with the origin of this or that flamenco form, but all is in Spanish so, given that each paper runs hundreds of pages, it is beyond me to try to analyze. But if they are similar to what is in his dissertation, I remember Ricardo was not very impressed in terms of musically-informed historical analysis. ; publications here: http://guillermocastrobuendia.es/publicaciones.html (all his papers available for free; just not the books). A lot of them seem to deal directly with the origin of this or that flamenco form, but all is in Spanish so, given that each paper runs hundreds of pages, it is beyond me to try to analyze. But if they are similar to what is in his dissertation, I remember Ricardo was not very impressed in terms of musically-informed historical analysis.

Anyway, the chronological table of Carlos Galán is based on his analysis and all this previous work, with detailed and specific footnotes/references; further/other details are typically in Castro’s papers. The Galán paper itself is freely available at http://www.sinfoniavirtual.com/revista/036/claves_flamenco.pdf (pdf)

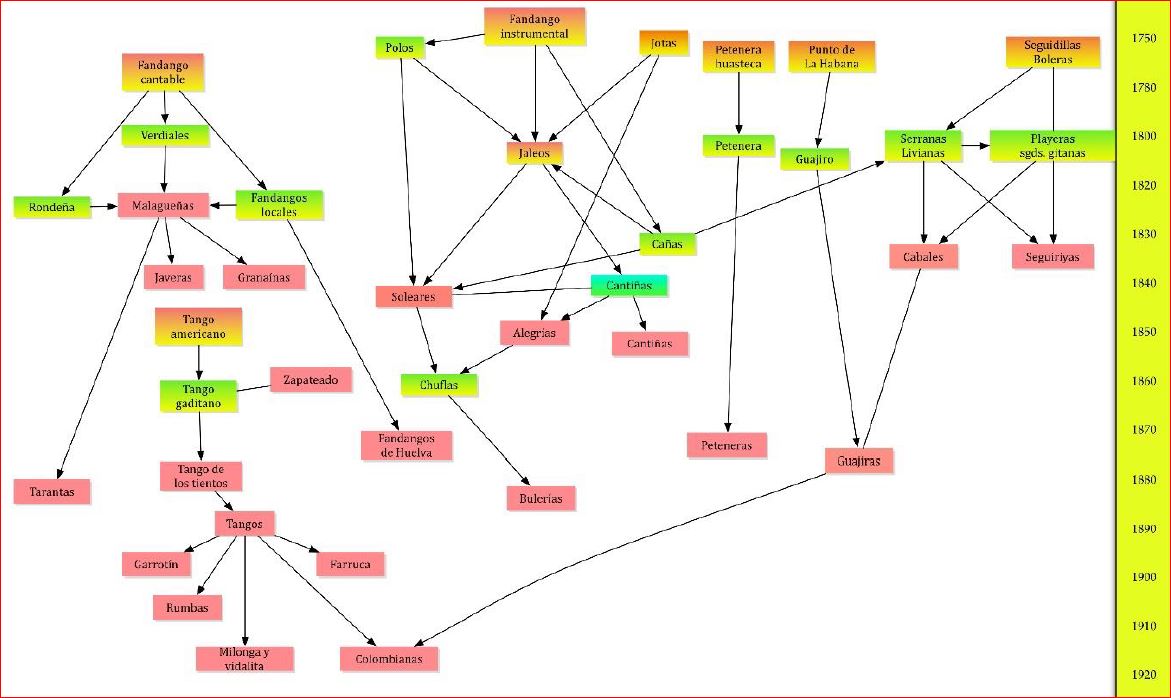

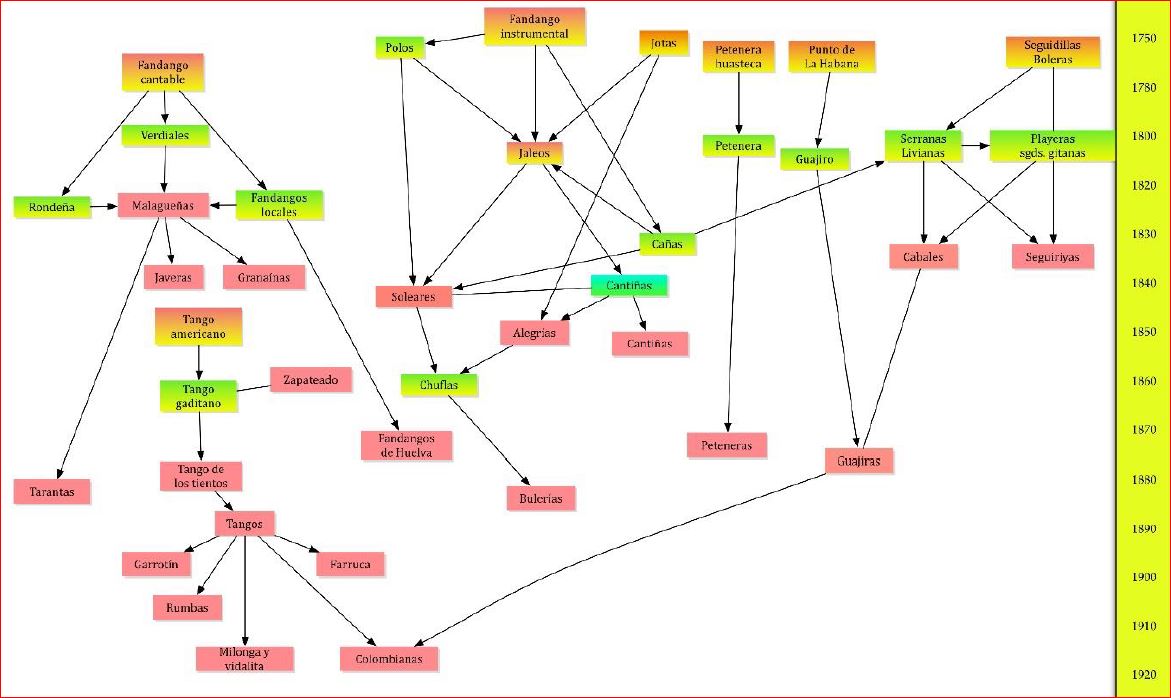

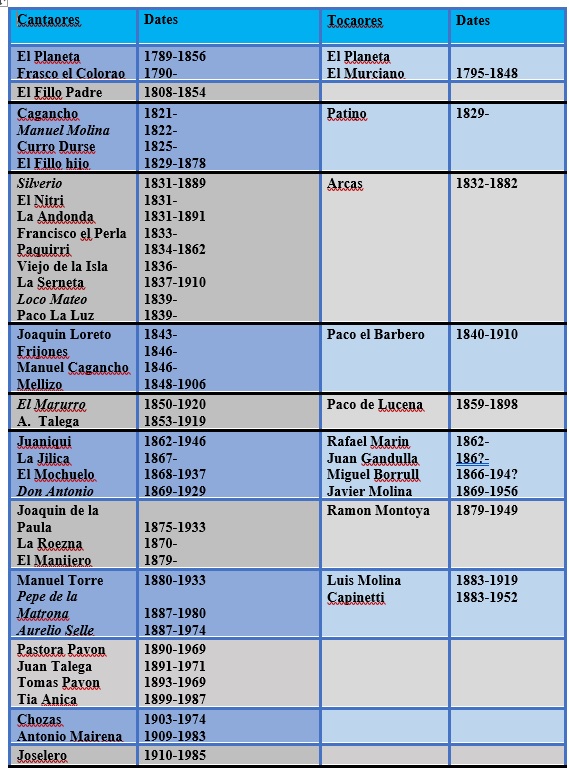

In summary it looks like this (this is all about the flamenco forms specifically):

1810s: Tonás

1820s: Rondeñas, Malagueñas y fandangos locales

1820s: Polos y Cañas

1830s: Cabales y Siguiriyas

1830s: Granaínas

1830s: Serranas

1840s: Cantiñas

1850s: Soleares

1860s: Alegrías

1863: Tarantas

1870s: Guajiras

1870s: Peteneras

1884: Tangos y Tanguillos

1890s: Tientos

1900s: Farruca

1900s: Bulerías

1904: Garrotín

1910s: Rumbas

1910s-1930s: Milongas, Vidalitas y Colombianas

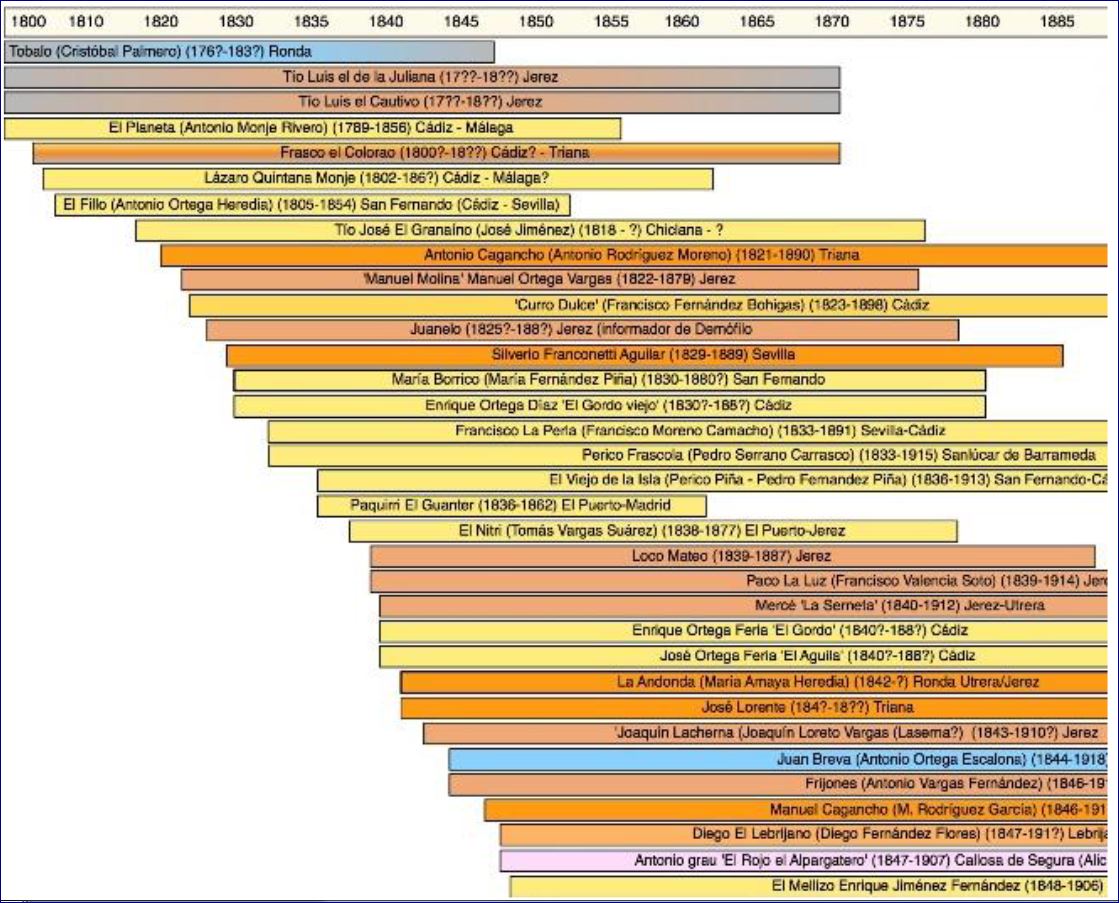

There is a graph of this which also shows the presumed connection to pre-flamenco forms. The solid red/pink are the flamenco forms; the orange and yellow are the folk forms; and I think green/yellow are transitional ones:

Images are resized automatically to a maximum width of 800px

Attachment (1) Attachment (1)

_____________________________

Konstantin

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 12 2021 18:39:48

|

|

kitarist

Posts: 1715

Joined: Dec. 4 2012

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

Yeah, though Galán does seem to acknowledge that there is a difference between relying on the label/name of a form itself to suggest provenance versus actually verifying that the form is musically the same or at least related in some provable way across time.

And I guess once we get into 20th century, due to recordings, it is much easier to make some informed musical arguments. So the biggest mysteries are still the ones about flamenco forms that emerged in the 19th century.

What about looking at a particular one - solea, say. Because with solea, it is not one of the cases where a folk dance/song existed by that name, so we would at least avoid that confusion.

I think Galán and the authors he references basically argue that solea emerged from a slowed-down jaleo performed by a single person (thus 'soledad' as a name). So this sounds, in part at least, like a musical argument; or at least implies one.

Here is Castro's paper from 2013 on this:

http://www.sinfoniavirtual.com/flamenco/jaleos_soleares.pdf

Could you (and of course, anyone else!) comment on what is good and bad about it and about the Galán little section about solea emergence in his paper; what did they get right and what did they get wrong, from your point of view?

_____________________________

Konstantin

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 15 2021 18:30:08

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14797

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist)

|

|

|

quote:

What about looking at a particular one - solea, say. Because with solea, it is not one of the cases where a folk dance/song existed by that name, so we would at least avoid that confusion.

My personal feeling is that it MUST have existed under a different working title (mainly because it is the biggest flamenco mother form from which other styles derive, next to fandango). I suspect polo Tirana or other options, including caña, as mentioned in the Escenas Andaluces book description of known flamenco cantaores performing and discussing cante. Solea apola, polo, Caña etc split apart later on as derivative styles. The attempt to label styles as we see on normans site, was an attempt to put the pieces back together, but it’s a confusing mess honestly.

I remember scanning that paper, I will check it again. But give me time.

At a glance here…page 3 he points out the same thing I noticed about Calderon book…the description of Caña has a lot in common with Solea. Of course that doesn’t mean much as Caña has so much in common anyway. But I pointed out earlier that, beyond what Castro buen dia shows, I noticed the “minor key” of the guitar and the way the letras were delivered probably refers to phrygian tonality, and more the way the letras and styles of Soleá letras are delivered than Caña specifically.

However to show a quick problem, on page 6 Castro buen dia translates your French dembowski book passage about Granada, the word FOLIA, into spanish Soleá!!!! That is a horribly misleading error of translation, as it implies in 1838 the word solea and folia were synonymous, and in fact he states earlier the earliest mention of Soledad baile was 1851!

So we must proceed with a grain of salt or fine tooth comb etc over this work. And to make it worse I can’t translate it because it is not words but a picture of words (pdf).

EDIT…oh darn, on page 7 he mentions the translation error. Ok…I will have to take time with this thing, sorry.

Images are resized automatically to a maximum width of 800px

Attachment (1) Attachment (1)

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 16 2021 14:27:35

|

|

Beni2

Posts: 139

Joined: Apr. 23 2018

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist)

|

|

|

quote:

What about looking at a particular one - solea, say. Because with solea, it is not one of the cases where a folk dance/song existed by that name, so we would at least avoid that confusion.

I think Galán and the authors he references basically argue that solea emerged from a slowed-down jaleo performed by a single person (thus 'soledad' as a name). So this sounds, in part at least, like a musical argument; or at least implies one.

No single author has a definitive argument on the solea's provenance in my opinion. Adding to the confusion is that "soledad" is an aesthetic that gives rise to multiple national genres around 1820 as Romanticism and Nationalism are emerging. Scholars working on Fado have many of the same problems that flamenco investigators do. Common ground is the saudade/soledad aesthetic. Soledades or cantos de soledad go back centuries on the iberian peninsula and some of the poetic meters survive in flamenco. Additionally, one singer refers to "playera" as a superordinate category, a generic style that is more or less coterminous with jondura. So you get Playera and Soledades as broad categories of melancholic "song." The seguiriya and soleares emerge from the more general categories as do others. The solea, in my opinion, is not the "mother" of other genres. Instead, many genres are still evolving by the time the first recordings emerge. Adding to all the confusion, any single genre might possess traces of multiple other genres. For example, a genre's poetry might originate in one line of genres, its rhythm in another, its harmony in another, its melodies in another, and its vocal form and content in another.

As for the playera/planidera hypothesis, I find it questionable. A playera is any song sung at the beach. Peoples' first intuitions usually reflect an association of the beach with joyous songs. But songs of mourning, nostalgia, or yearning are documented for sailors, warriors/soldiers, and peoples expelled from host countries (as the Jews and Arabs were in 1492).

This page is really helpful and useful in regard to the timeline. The discussion about "flamenco" could have been avoided by reading Steingress. Primary sources are important and necessary, but secondary sources sometimes provide exegeses of the primary sources such that an investigator does not have to reinvent the wheel. Just my opinion.

Finally, I don't agree with the "slowed-down" jaleo hypothesis. Listen to the earliest recordings and you get hints of bulerias. In fact, I would suggest that the bulerias only borrows the terceta/tercerilla from the solea. Its rhythm comes from the jaleo and the rhythmic cadences that punctuate the cante are still in flux/evolving in these early recordings.

Anyway, fruitful discussion.

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 17 2021 5:32:01

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14797

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to kitarist)

|

|

|

quote:

Actually this is one of the 'good' pdfs - probably because it was made recently from a Word document rather than scanned hard copy - you can select and highlight words and copy and paste into Google-translate as text.

The pdf I downloaded has a copy protection so I have to give a password to cut and paste. Not sure how you got around that.

Anyway, I was intrigued by the Ocon example from 1860’s. Castro buendia did his own arrangement which I dont’ get (EDIT I see he wanted to put solea compas counts in). The original book is great and far superior don’t know why he didn’t use it. 1874, and starting on page 80 to the end is hardcore flamenco transcriptions, which seems Ocon got right based on what I do professionally today. He lays out Fandangos and shows a melody that sounds familiar. The chord charts for guitar follow exact the structure for Malaguena/Rondeña (the cante that includes verdiales, fandango de lucena etc) and Murciana/Granaina. It reminds me of the Encuentro book of Merengue de Cordoba (2002 vs 1874, not any different 😂) He shows a malagueña melody which is basically Fandangos de Huelva type melody.

The SOLEDAD is a little fast (184bpm is a slow buleria, or very fast solea por buleria, Zyrab tempo range lol), and the cante that is sung is pretty darn close to Joaquin 2 as per Talega examples on Norman’s site. I have pointed out how that melody works for lots of standard fast buleria as well, so Ocon probably heard a fast version, or perhaps Solea was very fast back then. Important to note the cambio melody is typical of the type that don’t drop to E note but center around G. One of Talega versions does exactly the same thing. The significant thing is the delivery of lyric and repeats. Normally that melody is delivered straight through ABC no repeats, but Ocon’s version shows 4 line verse such that the the melody to call A minor cadence repeats (BB), then cambio and conclusion, CD, but the cambio repeats melodically more like a normal solea or buleria, yet with lyrics AB. Norman talks about how that works on his site. It I was just interesting to see it done with a melodic style that normally suites ABC format.

The Polo o Flamenco example is dead on Caña as I just performed it live two weekends ago!  But it is only the opening ay on the C chord and the first two letras. And the G chord thing is rushed where as it normally gets repeated and stretched, but it is clear as day to me the same cante. Normally there is one more letra and a “macho” which is to C major to G major, similar to Solea Apola conclusions. So as per our flamencology going on, polo and caña often get mixed up anyway, so maybe back then polo was catch all for all the Solea related forms? Luckily Ocon has other Polos in the book that prove the title is not that thing to look at, it is the specific structure. And to my eyes, this stuff was well in place already by this time period (1860-74). Considering he talks about “antiguo” melodies in the book, I am thinking ALL the singers on Romerito list knew about this stuff and were singing proper flamenco as we think of it today. But it is only the opening ay on the C chord and the first two letras. And the G chord thing is rushed where as it normally gets repeated and stretched, but it is clear as day to me the same cante. Normally there is one more letra and a “macho” which is to C major to G major, similar to Solea Apola conclusions. So as per our flamencology going on, polo and caña often get mixed up anyway, so maybe back then polo was catch all for all the Solea related forms? Luckily Ocon has other Polos in the book that prove the title is not that thing to look at, it is the specific structure. And to my eyes, this stuff was well in place already by this time period (1860-74). Considering he talks about “antiguo” melodies in the book, I am thinking ALL the singers on Romerito list knew about this stuff and were singing proper flamenco as we think of it today.

Finally that saeta and nana look pretty good too, I know those!!!!

http://www.bibliotecavirtualdeandalucia.es/catalogo/es/catalogo_imagenes/grupo.do?path=162199

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 17 2021 21:19:09

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14797

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Beni2) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Beni2)

|

|

|

quote:

In fact, I would suggest that the bulerias only borrows the terceta/tercerilla from the solea. Its rhythm comes from the jaleo and the rhythmic cadences that punctuate the cante are still in flux/evolving in these early recordings.

I agree with all you wrote except for this thing here. Im ready for a 10 hour conversation about this!

But seriously, I used to not understand the connection directly between solea and buleria, except 12 counts, until I got into cante. Now I don’t understand why Bulerias corta larga, sordo la luz, etc, are not considered Solea styles as they fit right in. Also polo and Caña, although, I forgot to point out earlier the way the lyrics are delivered is different, with the lamento Ayeo thing cutting into to the structure. And the apola and solea petenera thing, and after all the darn petenera that I had avoided listening to for 20 years lol. All are types of “solea”, or rather, fit that structure and hence get linked together in performance.

But anyway the thing about solea and buleria, and tiento tango for that matter, is the STRUCTURE and how the melody is designed to call in the cadences that retain that structure and finally the lyrics are plug and chug for all, and the way the dances tie it all together with a neat little ribbon. If anything Jaleo, as in extremeños, has the odd ball chord structure and melody. See jerez anonymous on Norman’s site. Nothin about that structure in Castro Buendia’s article either.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 17 2021 21:33:47

|

|

Beni2

Posts: 139

Joined: Apr. 23 2018

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

quote:

I agree with all you wrote except for this thing here. Im ready for a 10 hour conversation about this!

But seriously, I used to not understand the connection directly between solea and buleria, except 12 counts, until I got into cante. Now I don’t understand why Bulerias corta larga, sordo la luz, etc, are not considered Solea styles as they fit right in.

You're still looking at it from a modern perspective. I am saying to go to those early recordings. Those guitarists are still figuring stuff out. If you listen to the soleares from 1895-1908 it is obvious the forms (i.e. compas, remates, cierres, chordal accompaniment, etc.) are not fixed yet. There are a few of those recordings that stay in 3/4 (×2 = 6/4) until the vocals resolve; the guitarists switches to 3/2 for the cierre and then goes back to 3/4.

That does not answer our questions (completely) about the origins or etymology though. Ready for that discussion?

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 17 2021 23:52:35

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14797

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Beni2) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Beni2)

|

|

|

quote:

You're still looking at it from a modern perspective. I am saying to go to those early recordings. Those guitarists are still figuring stuff out. If you listen to the soleares from 1895-1908 it is obvious the forms (i.e. compas, remates, cierres, chordal accompaniment, etc.) are not fixed yet. There are a few of those recordings that stay in 3/4 (×2 = 6/4) until the vocals resolve; the guitarists switches to 3/2 for the cierre and then goes back to 3/4.

I have no other perspective than modern, however, trying to be objective I see that things didn’t evolve much. Now, I think we argued to a dead end point about some solea wax cylinder thing in the past where YOU hear basic 3/4 vague accompaniment as evolutionary stepping stone, where I heard a lucid half-compas cambio or some-such-complex-thing in the same example. I tried to demonstrate these concepts in the cante accomp thread many years ago with the moneo and donday examples, but not sure everybody was onboard with me or understand the point there. The Carol Whitney score of Talega also clearly shows this concept. This ties in directly to old arguments we had about elastic compas, half compas etc.

The thing I keep arguing is that the cante melody is traditionally allowed to de-couple from the compas, such that guitarists have learned a system to create the structure via compas accent and cadences AROUND that loosely-timed delivery of verse. A lot of emphasis or problem centers on the cambio or relative major cadence. The buleria larga with the “zero verse” extension seems designed to repetitively teach this concept, though we see it can occur in solea based forms at anytime without any extensions of lyrics. I pointed out a Mairena example crossing the bar line , but again I am not sure everybody is on this exact same page with me cuz it was a dead end argument as well.

While the wax cylinder example served to inform ME (regardless if we keep arguing about what we hear there) that this situation was known before Melchor or a n. Ricardo managed to blue print it (vs the half compas cutting option we occasionally see w montoya or carrion), I totally stand corrected about a score not existing before that time. The Ocón score of Soledad manages to capture and prove concretely that this exact concept (he places the FIRST C major cadence late at the 1,2,3, the second at 10 as normal), I am discussing, was WELL established by 1860s….so Melchor and ricardo were not setting a precedent, they were following an ancient tradition already in place. A further detail is the half compas Ocon allowed to occur at the repeat of the B verse (A minor cadence). We can imagine that the singer came in on 9 instead of 3 there. Yet another detail is F major7 is used instead of A minor for that cadence. How the guy captured all this nuance without a tape recorder and slow downer, is scary. (Castro buendia missed a passing tone G# at the first Cambio, but that is a minor error). Regardless, it stands as a testament that the basic cante and accompaniment of Soleá had all the important boxes checked, LONG before the first wax cylinders.

To my mind, I’m certain that one or more of those strange song forms mentioned in Calderon book (1838) was the old working title of the solea/buleria before the Soledad title got attached to it. Since the Ocon book shows that polo flamenco was Caña, maybe Caña as described then, was Soleá? Castro buendia also points the description of it as sounding similar ( I said that earlier too).

Forgot to mention Ocón also shows that “seguidilla Sevillana” is the old Garcia Lorca sevillanas we hear in the Saura movie, or the paco/modrego duets, etc.

Oh forgot Andonda is born 1831 or 1842? Serneta 1831 or 1837??? 😂

And the segovia transcriptions were fun to see in the appendix of Castro buendia.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 18 2021 14:11:42

|

|

Beni2

Posts: 139

Joined: Apr. 23 2018

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

quote:

I have no other perspective than modern, however, trying to be objective I see that things didn’t evolve much. Now, I think we argued to a dead end point about some solea wax cylinder thing in the past where YOU hear basic 3/4 vague accompaniment as evolutionary stepping stone, where I heard a lucid half-compas cambio or some-such-complex-thing in the same example. I tried to demonstrate these concepts in the cante accomp thread many years ago with the moneo and donday examples, but not sure everybody was onboard with me or understand the point there. The Carol Whitney score of Talega also clearly shows this concept. This ties in directly to old arguments we had about elastic compas, half compas etc.

I get your half-compas idea. That's basic. Those early recordings show that most of the singing and accompaniment is in two measure groupings of 3/4 only switching to a 3/2 to punctuate the cante with a cierre. We are saying the same thing almost. I am just pointing out that the hemiola is not THE ORGANIZING principle. Heck, most people don't even know what a hemiola is. How one defines it will definitely shape how you thinks about things like the evolution of the cante, the accompaniment, and whether or not the buleria is an offshoot of the solea or not, or to hat extent it did inherit musical/poetic features (I am in the latter camp).

quote:

The thing I keep arguing is that the cante melody is traditionally allowed to de-couple from the compas, such that guitarists have learned a system to create the structure via compas accent and cadences AROUND that loosely-timed delivery of verse. A lot of emphasis or problem centers on the cambio or relative major cadence. The buleria larga with the “zero verse” extension seems designed to repetitively teach this concept, though we see it can occur in solea based forms at anytime without any extensions of lyrics. I pointed out a Mairena example crossing the bar line , but again I am not sure everybody is on this exact same page with me cuz it was a dead end argument as well

I also get this point. I am suggesting that one line of musical evolution sets the poetic texts mostly syllabically. I think it is a mistake to look at early versions of cantos andaluces and write them off as imitations of flamenco. Everything was in flux. So my point is that, contrary to popular opinion, the texts were geared toward baile. But a second line of singing emancipated the texts from strictly syllabic and baile-oriented. THis is not such a problem in 3/4 time. The guitarist could keep chugging away.

In an Occam's razor argument, I would suggest that it is much more likely that the poetry went from simple syllabic and danceable (although there were other ways of singing that coexisted with roots in gitano, arabic, and sephardic singing), to more complex. Hepta and octosllabic poetry fits nicely over 6/4 with its last syllables manipulated to reflect the hemiola. Its a short skip to get to melismatic and neumatic decoration. This suggestion does not counter your points. It fits with them. The only difference is it counters the myth that the cante was first (did Planeta have a muscal instrument?).

quote:

The Ocón score of Soledad manages to capture and prove concretely that this exact concept (he places the FIRST C major cadence late at the 1,2,3, the second at 10 as normal), I am discussing, was WELL established by 1860s….so Melchor and ricardo were not setting a precedent, they were following an ancient tradition already in place.

I'll look at the Ocon but if its still evolving on those early recordings I would not call it a tradition. Hurtado Torres and others warn not to read too deeply into the scores and you yourself have said going back earlier than recordings is speculative.

quote:

Oh forgot Andonda is born 1831 or 1842? Serneta 1831 or 1837??? 😂

Yeah. There are problems with some of the sources. I was working of notes taken from Alvarez Caballero, Kliman's site, and el arte de vivir flamenco site. Glad you brought that up because you mentioned that you thought Andonda was the earliest singer of solea. Nunez notes at his site that Gamboa thinks Paquirri is and that it spread from Cadiz to Jerez and then Sevilla/Triana.

Gonna go lookk at the Ocon.

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 18 2021 19:58:28

|

|

Ricardo

Posts: 14797

Joined: Dec. 14 2004

From: Washington DC

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Beni2) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Beni2)

|

|

|

I agree with you hemiola is not the organizing principle, I agree the idea the verse went from simple to complex delivery, also that baile shows that simplicity, but not necessarily gave birth to the syllabic basis of the verse. 8 syllable stuff is OLD!!! 😂. I also agree that Planeta played guitar so cante could be as OLD as guitar, or rather, accompaniment with a guitar might have been there at the start. It is simply true that not everybody could afford one that sang those songs.

quote:

Hurtado Torres and others warn not to read too deeply into the scores and you yourself have said going back earlier than recordings is speculative.

I agree with him in most cases. But frankly it is shocking to see that Ocon book, never would have thought it could exist, I eat crow on that point. To capture ABCD lyric mix over a three line melody (Solea corta), with half compas option explored on repeat, extended cambio, cambio variant, etc, it is like too good to be true in that little diddy, plus the song title ties the form to its known form name today (arguably bulerias/Solea or solxbul etc, however).

The Ocon guy either 1) had a photographic memory, 2) the performers he observed were able to repeat an improvised performance over and over the exact same way, or 3) he was actually a knowledgeable flamenco guitar accompanist himself and deliberately chose to encapsulate in score form a “perfect” example of what was going on for posterity.

quote:

Glad you brought that up because you mentioned that you thought Andonda was the earliest singer of solea. Nunez notes at his site that Gamboa thinks Paquirri is and that it spread from Cadiz to Jerez and then Sevilla/Triana.

I read it somewhere. I don’t believe she was the first at all, nor do I think Paquirri the 11 year old invented it (Gilliana or Jaleo= solea is the thought there). The point was I thought it was KNOWN that the song TITLE “solea” or “soleares” or “soledades” was first attributed to Andonda’s first known performance of it. Surprisingly Castro Buendia does not mention her name in that entire paper on the subject, which I assume means the claim is anecdotal, baseless, OR, proven wrong somewhere? He shows how it (Soledad) vaguely appears in print 1851ish and it is not clear any known flamenco singer sang it until an 1856 attribution to “Tio Planeta” in Malaga (he was dead or died that year?), implying that the form, unlike some older ones, was not yet fully formed, or understood.

My thoughts are that it WAS formed long before this evidence, and that it simply was under a different working title.

_____________________________

CD's and transcriptions available here:

www.ricardomarlow.com

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 18 2021 21:20:41

|

|

kitarist

Posts: 1715

Joined: Dec. 4 2012

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

quote:

Oh forgot Andonda is born 1831 or 1842? Serneta 1831 or 1837???

La Serneta is La Andonda's senior by 8 years and apparently she is the one considered "the mother of solea" so to speak; the fact that she is eight years older also agrees.

La cantaora y guitarrista María de las Mercedes Fernández Vargas, Merced la Serneta, was born Mar 19, 1840 in Jerez (where she lived at least until 1881) and died Jun 12, 1912 in Utrera.

Very well researched and referenced here with tons of other details: https://www.flamencasporderecho.com/merced-la-serneta/ so no doubt at all about the exact dates.

Also, apparently there is a notice in the newspaper 'El Progreso' from 1888 attesting to her already being widely recognised as a master and her personal song style admired and sought after.

Same researcher states that María Amaya Heredia, La Andonda, was born in 1848 in Ronda. See in particular page 164 of this article:

RODRÍGUEZ, Ángeles CRUZADO. 2016 "Female flamenco artists: brave, transgressive, creative women, masters... essential to understand flamenco history."

https://www.flamencasporderecho.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Forum_Fil_2016_A-Cruzado.pdf

Also from that article:

"Merced la Serneta [..] gave guitar and singing lessons to Madrid high society families."

EDIT: See followup below, Andonda born on Aug 29, 1843 (so Serneta is her senior by three years, not eight)

_____________________________

Konstantin

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 19 2021 0:20:58

|

|

Beni2

Posts: 139

Joined: Apr. 23 2018

|

RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo) RE: Flamenco-related Timeline 1740 -... (in reply to Ricardo)

|

|

|

quote:

I agree with you hemiola is not the organizing principle, I agree the idea the verse went from simple to complex delivery, also that baile shows that simplicity, but not necessarily gave birth to the syllabic basis of the verse. 8 syllable stuff is OLD!!! 😂. I also agree that Planeta played guitar so cante could be as OLD as guitar, or rather, accompaniment with a guitar might have been there at the start. It is simply true that not everybody could afford one that sang those songs.

So is five and seven syllable. I think too much emphasis is put on that, although seven or eight syllables does fit nicely over two measures with room to decorate the last two syllables in a hemiola. quote:

I agree with him in most cases. But frankly it is shocking to see that Ocon book, never would have thought it could exist, I eat crow on that point. To capture ABCD lyric mix over a three line melody (Solea corta), with half compas option explored on repeat, extended cambio, cambio variant, etc, it is like too good to be true in that little diddy, plus the song title ties the form to its known form name today (arguably bulerias/Solea or solxbul etc, however).

The Ocon guy either 1) had a photographic memory, 2) the performers he observed were able to repeat an improvised performance over and over the exact same way, or 3) he was actually a knowledgeable flamenco guitar accompanist himself and deliberately chose to encapsulate in score form a “perfect” example of what was going on for posterity.

I agree, its an amazing document.

quote:

I read it somewhere. I don’t believe she was the first at all, nor do I think Paquirri the 11 year old invented it (Gilliana or Jaleo= solea is the thought there).

I just read it in Alvarez Caballero. Pg 64. He discusses La Andonda as el Fillo's partner and suggests that if she was not "a creator" (he does not say "the creator"), she helped to popularize it.

At Konstantin: Same page (64), AC suggests that the cantes of Serneta bear traces of La Andonda "lo que tambien creia Juan Talega."

It has been conventional wisdom that Andonda was the earlier figure. I stand corrected but it is something most aficionados still believe. Only scholars, aficonados, nerds, and aficionado-nerd-scholars will adjust. But I will look into that more.

Galan has her b.1840. But this raises interesting questions about her affair with el Fillo. El Fillo Padre was born 1805, hijo 1829 (Galan does not een acknowledge him - to be fair, either does ACaballero; Andalucia.com dates his birth at 1820). Not likely that la Serneta was with Fillo Padre. Insignificant as a focal point, but with so many attributed dates, the potential for major mistakes mounts.

@Ricardo: Castro Buendia, this scholar that Konstantin cited, and many others are citing the last third or even two decades as the time of "birth." "From its birth, in the last third of nineteenth century, and during the first decades of the twentieth,

flamenco has..." This is how she begins her abstract. To say that most scholars take the latter part of the century as flamenco's time of emergence would be an argumentem ad populem but sometimes strength in numbers comes from the data and the reasoning behind any conclusions based on that data.

|

|

|

|

REPORT THIS POST AS INAPPROPRIATE |

Date Nov. 19 2021 1:01:56

|

|

New Messages New Messages |

No New Messages No New Messages |

Hot Topic w/ New Messages Hot Topic w/ New Messages |

Hot Topic w/o New Messages Hot Topic w/o New Messages |

Locked w/ New Messages Locked w/ New Messages |

Locked w/o New Messages Locked w/o New Messages |

|

Post New Thread

Post New Thread

Reply to Message

Reply to Message

Post New Poll

Post New Poll

Submit Vote

Submit Vote

Delete My Own Post

Delete My Own Post

Delete My Own Thread

Delete My Own Thread

Rate Posts

Rate Posts

|

|

|

Forum Software powered by ASP Playground Advanced Edition 2.0.5

Copyright © 2000 - 2003 ASPPlayground.NET |

0.125 secs.

|

Printable Version

Printable Version

; publications here:

; publications here:

New Messages

New Messages No New Messages

No New Messages Hot Topic w/ New Messages

Hot Topic w/ New Messages Hot Topic w/o New Messages

Hot Topic w/o New Messages Locked w/ New Messages

Locked w/ New Messages Locked w/o New Messages

Locked w/o New Messages Post New Thread

Post New Thread